There is no greater mystery than a person’s life.

We are all a web of insurmountable secrets. The tall task of movies is to find an engaging way to present us in all of our complexity. An even taller task falls upon biopics; films that are meant to tell the life of an important/remarkable human being. Not only is it a great responsibility to depict truthfully the key events in someone’s life; it is arguably even more important to reveal a person’s colors without making them bland or predictable in the eyes of history. What’s more disappointing than when a film cannot match the grandiosity of the person whose life story it decides to tell?

People who know me know how much I generally dislike biopics. I tend to avoid them like the plague. The film industry churns out dozens of them every year with very little regard for quality or actual depth in storytelling. Most are laughably bad and function like visual aides to Wikipedia entries. Surface-level material that relies on make-up and performance to add credibility to its shallow presentation.

But every now and then, a good one slips out. Sometimes invertedly so. Sometimes, against all-odds, a biopic finds a way to reckon with the singularity of the person and time it is depicting. Such is the case of James Mangold’s A Complete Unknown – a film that made me reconsider the way a person’s life can be told in the modern Hollywood system.

The film obviously does not need an introduction. It’s a high-profile, multi-million production that earned several Oscar nominations, starring one of the biggest stars at the moment in Timothée Chalamet. It focuses on one of the most iconic figures of American music in Bob Dylan and on one of the most eventful time periods in recent memory. And yet despite all of this, the film maintains a kind of pure intimacy that I have not come to expect from this particular genre of cinema. Above all, it is a film that knows how to preserve the secrecy around its main protagonist and avoid spoiling the magic that we associate with the impenetrable soul of Bob Dylan.

One must always approach the subject as impossible to define in its totality. Films that pretend they can do the absolute and unveil every secret of a person’s life fail every time. Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer was a success because it offered us impressions of its titular character rather than bullet points from his tumultuous and complicated life. But unlike Robert Oppenheimer, who was haunted for most of his life by several clearly defined traumas, Bob Dylan never let on what haunted and continues to haunt him to this day.

That is the way James Mangold – one of Hollywood’s most accomplished journeymen directors working today – set out to tell Dylan’s story: by knowing right from the start that there is no way to access the songwriter’s deepest truths. That there is no such thing as encompassing his biggest secrets in a two-hour movie.

And that is how A Complete Unknown starts: with a vague impression of a young kid with a guitar, starved for a fulfilling, successful career. Right from get-go we know what Dylan wants, and that is to be great. He appears before us like a vision with no place to call home. When asked where he’s from he only says “The Midwest” before proceeding to tell stories about how he toured the country with a carnival. That’s as close as we are going to get to the truth with Dylan.

Unlike Mangold’s previous musical biopic, Walk the Line; about Johnny Cash’s love life and his struggle to emerge from the clutches of the trauma from seeing his brother die at a young age; A Complete Unknown rejects the study of the past of its main subject. Instead, it settles for an exploration of the world Dylan inhabits, or rather, comes into contact with the moment he steps into the streets of New York in 1961.

Dylan, like the ghost that he is, arrives in New York at a breaking point in history. It is the birth of the Civil Rights Movement. It is the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis. It is time of change, of people awaking from the slumber and comfort of 1950s suburbia. And Dylan falls in the midst of this societal revolution. But he is not the only one: the music landscape of the time is filled with people like Joan Baez, Johnny Cash, Dave Van Ronk, Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie. People of different times, different credos, with different agendas. Mangold knows that the key to telling Dylan’s story is to tell it through the eyes of those that watch him perform, those who get to watch the genius emerge and flow onto the stage.

The first hour of the movie is purely impressionistic and free-flowing. Not for nothing Mangold’s model while writing the script was that of a Western – the stranger walks into town and is immediately surrounded by the town’s locals who all want something from him. In other words, he follows the oldest story in the book while trying to create a palpable world surrounding the mysterious protagonist.

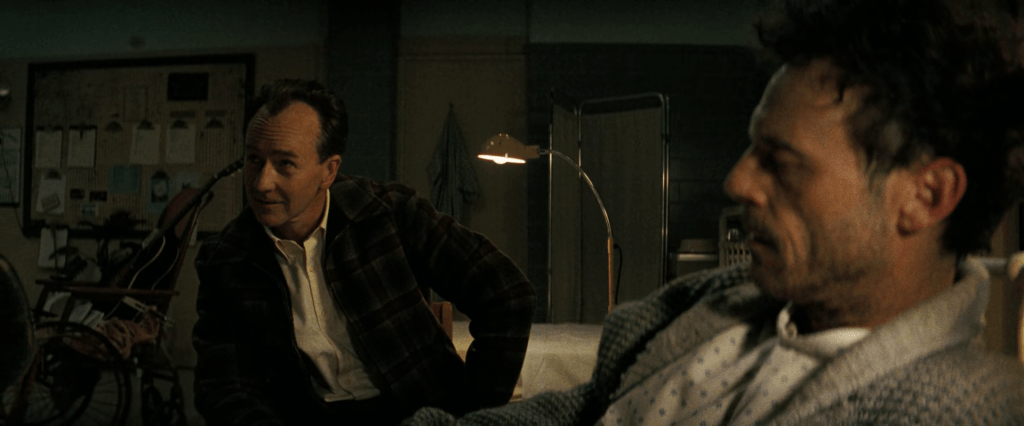

At first, Chalamet’s performance as Dylan appears borderline cartoonish. He grunts and mumbles and in the moments where you expect him to come through clearly, boldly, he does the opposite and shrinks, almost disappears off the screen, allowing everyone else to crowd him. But over the course of the movie’s runtime that becomes the focal point of Mangold’s picture: the overbearing agendas hanging over a kid who just wants to write and play his own music. The entire point of Dylan coming to New York is to see his idol, Woody Guthrie, who is dying in a hospital. His purpose is as simple as that. And yet, people can see that there is more to him. That the gods have placed their truths inside this human vessel. This prophet who appears at the right place, at the right time. That is the case for his mentor, Pete Seeger (played by Edward Norton), who immediately tries to impose his world view on Dylan – that real music is folk music, a good song does not require any frills in order to be good, that rock ‘n roll does not serve any higher purpose than mere entertainment. “Yeah, but it sounds good,” replies Dylan.

Mangold’s decision to commit to Dylan’s personal life first and foremost, like in the case of Johnny Cash’s story, allows for a deeper exploration of his music. The focus of the film is placed on life on the stage, where the artists – carnival freaks, as Dylan calls them – are called to bare themselves. “You can be ugly, you can be beautiful, but you can’t be plain,” he tells his girlfriend. “You gotta be something people can’t stop looking at like a train wreck or a car crash.” And that’s exactly what Mangold and Chalamet agree on; to make Dylan’s importance to music felt by focusing on his impact on the others around him. And the stage becomes an arena for feelings to come spilling out. Whether it’s love, anger or sadness, it all lives and dies on the stage.

A Complete Unknown observes the way Dylan is able to have everyone fall in love with him despite being afraid or envious of his genius. Fittingly enough, Mangold cited Milos Forman’s Amadeus as a huge influence in the way the film’s script was structured for we learn about Dylan by following his ghost in the lives of those that, like Salieri, become intoxicated with his brilliance and can’t look away, even if the mere act of looking is a painful one.

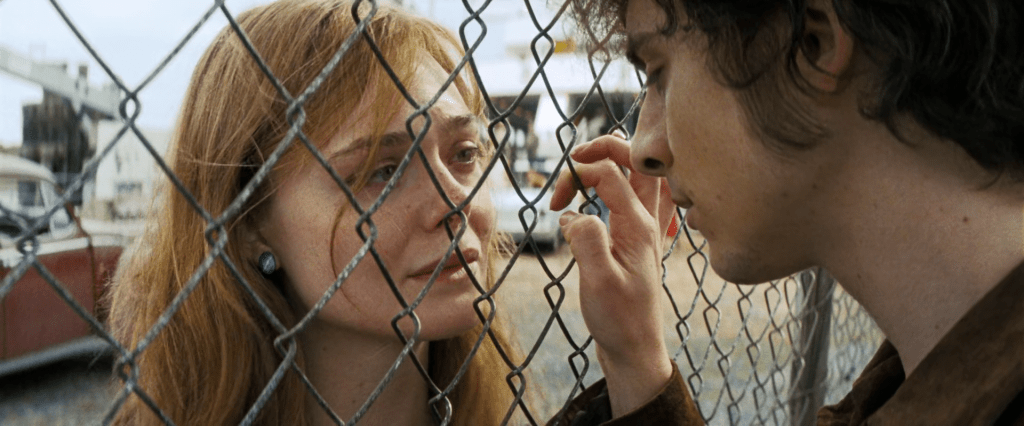

The clearest example of this is a beautiful sequence at the movie’s halfway point, when Sylvie (played by Elle Fanning) realizes she cannot be with Dylan. That no matter how much she loves him, how much she wants to make things work with him, he will always be in a separate world from her, a world that will remain inaccessible for as long as she keeps him in her heart.

The sequence takes place at the first Newport Festival Dylan attends. Sylvie sits to the side of the audience and witnesses Bob take on the weight of the world and lift it effortlessly, by singing “The Times Are A-Changin’” and earning the adoration of the crowd, Seeger, Baez, and all the people who claim to know what real music is all about. And while Bob performs and the people cheer and clap, Mangold keeps his camera steady on the faces of the on-lookers, including Sylvie whose eyes begin to fill with tears. Then, as if spurred by a voice inside her head or heart, she steadies herself, looks down, then raises her head in acceptance. There is nothing she can do to contain him. He will be carried away from her whether she likes it or not.

What is most striking about the film is that we are never let in on Dylan’s big secret. There is no pay-off. No big reveal. Perhaps because there is no secret. Perhaps because in Dylan’s case there is no trauma, there is no root cause for his being. Sure, there is a brief moment where we get a glimpse of him receiving letters addressed to a ‘Robert Zimmerman’, possibly hinting at a troubled past identity, but beyond that we are given no insight into who this man is. Giving it away would have cheapened the film and gone against Dylan’s entire credo as an artist. Perhaps his only suffering stems from the genius that everyone recognizes in him. That is his curse, the beast of burden that inspires others to project their own dreams and aspirations onto him.

To counter the scene in which Sylvie falls out of love with Dylan’s myth, Mangold includes a beautiful moment in which Joan Baez falls for him. It is when the Soviet threat of a nuke potentially targeting New York has everyone running around the city in panic, including Baez who packs her bags and guitar and starts looking for a taxi to get her out of the city. On her way to the taxi stand she overhears a familiar voice which prompts her turn around and inspect where it’s coming from – it is Dylan, sitting in a basement, in front of a small crowd of people, singing “Masters of War”. It is in that moment that Baez falls in love with him and what he stands for – artistic excellence in the face of annihilation. What’s the point of running when you have a guitar and you can sing, and can make people feel safe by doing so? That is Dylan’s burden – that he reminds everyone what they could and should be doing.

Than God for movies like A Complete Unknown: imperfect reminders that movies come from a place of mystery. That sometimes all we have to do is capture the spark of a man sitting at a desk, writing a song that could prove life-changing for a million others. Dylan’s life was never meant to be analyzed or dissected. At most, it was meant to be admired from afar, keeping us puzzled, hesitant, or freaked out that someone can just appear out of nowhere and conquer the world with their own singularity. Sometimes even just witnessing another man’s greatness can save a life.