A few days ago we sadly lost someone who, for my money, is the best actor this world has ever seen. The power Gene Hackman exuded on screen remains unparalleled to this day. Few actors could make the action pop the way this burly fellow from San Bernardino, California could, and even fewer could walk the line between comedy and terror the way he did.

For several decades, Hackman did it all: he was the brute, the sidekick, the veteran, the lunatic, the wise old man, the gangster, the outlaw, the sheriff and the erratic, selfish father figure. For God’s sake, he was Lex Luthor! He could love and hate like nobody’s business. He used to say, “The difference between a hero and a coward is a step sideways,” and lived by what he preached; his characters always felt like they could have easily found themselves on the opposing side of the fence had circumstances been slightly different. They were never predictable, always believable and earnest, to the point that I even sought out some of Hackman’s worst films – there’s not a single bad performance in any of them. In the 80s, after his Oscar glory from The French Connection had faded, Hackman resorted to doing a lot of questionable films for a paycheck – as trite and stupid as some of them are, Hackman never stumbles. Instead, he always seems to find a way to hook the viewer with his sheer explosiveness and grit. His desire to make us, the audience, care.

That is why today, to honor Hackman’s memory, I will turn to one of his last great performances prior to his decision to retire, and one that serves as a perfect summary of Hackman’s talent as an actor.

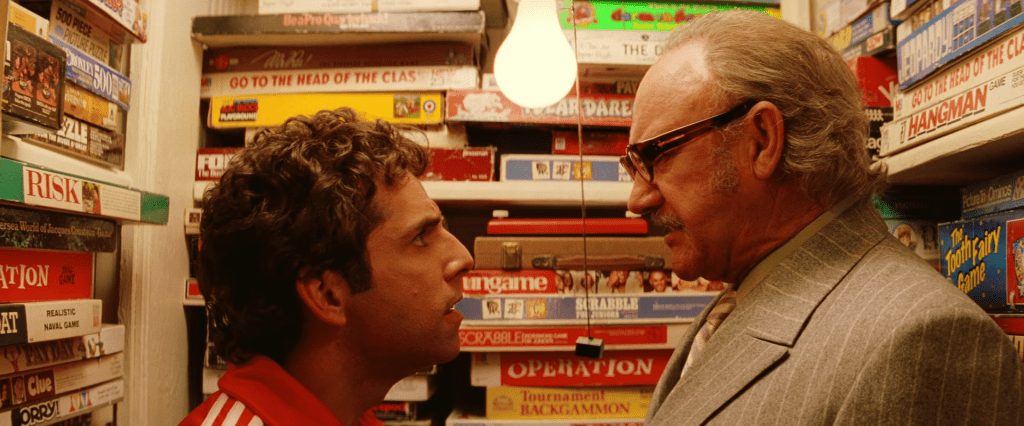

Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums saw Hackman win a Golden Globe at the age of 72 in an unexpected turn of events considering the actor himself did not think much of the movie at the time of its making. The film – a hilarious and moving saga about a family of tormented geniuses – forced Hackman to do things he didn’t feel confident enough in doing. It required him to change his rhythm and tone, and adapt to Anderson’s distinct vision. These demands spooked the veteran actor who famously bullied the young filmmaker throughout the whole shoot, to the point that Bill Murray had to come to Anderson’s defense (and openly called out Hackman years later). But what we got in return is a beautiful performance that gave Hackman the chance to bid his farewell to the world of movies, seeing as less than three years later he announced his retirement.

In the film, Hackman’s Royal Tenenbaum is a walking disaster: an amalgamation of various characters in Hackman’s career all balled up into one selfish, pig-headed individual whose priority remains saving his own ego and maintaining control of his family. When confronted with the news that his ex-wife (Anjelica Huston) might remarry, Royal pounces at the opportunity of re-inserting himself into the lives of his miserable family. His children hate him, his wife hasn’t spoken to him in seven years and he has no idea what the names of his grandchildren are – to make it short, Royal is not popular among the Tenenbaums. Yet, in typical Hackman fashion, his character makes us reconsider all of the assumptions that are made about him. Soon, we find ourselves drawn to him, hypnotized by the charm and charisma of the hip old man who doesn’t take ‘no’ for an answer and who makes it his mission to reconnect with his long-lost relatives.

And so it begins. Royal starts to plan his comeback to the Tenenbaum household. After 22 years of living in a hotel room, he moves back into his former residence, passing himself off as a dying cancer patient. A reckless, egotistical son of a bitch, that’s who Royal is. But that’s not all he is. Because deep down, even in the guts of a selfish old goat like Royal there is an ounce of humanity and goodness that genuinely begs for a second chance from his loved ones. While under the semi-illusion of his approaching, made-up death, Royal tries to ingratiate himself with his children. However, the scars he left on them appear too deep, too profound to be resolved at the drop of a hat. It finally dawns on Royal that not everything can be saved – some things will remain unchanged until the end of time.

Or will they? That is the beautiful thing about Wes Anderson and Gene Hackman’s collaborative creation. Hackman’s bullying of Anderson – well documented on several behind-the-scenes videos available on YouTube – could be interpreted as the actor’s fear of falling into grotesque, caricatural territory. The fear of appearing false was the most frightening prospect to an actor like Hackman who based his entire work on the premise that every character, good or bad, deserves a chance. To make Royal a cartoonish figure would have equaled the worst kind of betrayal for an actor. What Hackman did not realize is that his own persona and Anderson’s penchant for eccentric and silver-tongued characters made for the perfect collaboration. This is most evident when Royal finally understands that trying to make amends signifies actual change and, as a result, decides to spend time with his two grandsons. All of a sudden, this tyrannical father figure turns into a lovable ‘pappy’ as Royal takes the two boys on countless adventures – “I’m not talking about dance lessons,” he tells them, “I’m talking about putting a brick through a guy’s windshield, I’m talking about takin’ it out and choppin’ it up.”

There is such an earnestness in Hackman’s voice as he delivers this or many other lines of this kind that make impossible not to fall for Royal’s attempt at patching things up with his family. Even when his made-up illness is revealed, Royal is still able to come through with a hard-hitting realization.

“You know, Richie, this illness, this closeness to death… it’s had a profound affect on me,” he tells his son.

“But that Dad, you were never dying.”

“But I’m going to live,” says Royal, with the unmistakable Hackman grin that could very well stand for a teary eyed expression in any other actor’s repertoire.

Because what dawns on Royal is also the fact that life can be lived well, with meaning, with love, with care for others; something that had never occurred to him before. When his wife asks him why he didn’t care about them all these years, Royal simply replies, “I don’t know,” but the truth is that he’s just as frightened by this pathetic explanation. How can a man live sixty-plus years and not see the damage he’s done all around him?

Hackman meets Anderson’s writing halfway and imbues it with a sense of earnest authenticity – like a film actor walking onto a theater stage and grappling with some of the Bard’s work. His hesitance in fully committing to the director’s vernacular makes him dig even deeper into his own ego. Hackman’s frustrations spill out onto the screen as Royal learns to take notice of others’ suffering. His growth parallels Hackman’s own trajectory in adapting to Anderson’s material and learning to read between the lines, which is where most of Anderson’s gems are – right beneath the surface, where we least expect them. Like when the camera closes in on Royal’s face as he says, “Look, I know I’m going to be the bad guy on this one, but I just want to say the last six days have been the best six days of probably my whole life,” which is followed by the narrator telling us, “Immediately after making this statement, Royal realized that it was true.” In that very moment, Hackman’s face does a very slight, almost imperceptible twitch. The smile on his face freezes, as if seized by sudden paralysis. Other actors would have played it for show, whereas Hackman plays it for real.

Royal’s progression toward enlightenment and self-reflection could not have happened had Hackman not been the kind of actor he is. These moments of self-discovery would not ring true had someone else taken over his role (say, even Bill Murray – a loyal Anderson regular). They come across as the highlights in a movie that is about small, brief moments packing a potent punch because Hackman is discovering himself as a performer. It is all new to him, much like it is all new to Royal. At this stage in his career, Hackman had nothing left to prove – he had won his second Oscar for his supporting turn in Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven and was ready to call it quits in the absence of stimulating offers. And yet, Anderson was perhaps the only filmmaker with a singular voice that was distinct enough and at odds with Hackman’s overall body of work to make him want to get back into the swing of things. This clash of attitudes and beliefs produced a film of absolute honesty. Because that’s what Hackman’s work was all about – honesty, at all times. Honesty that assumed a multitude of shades, all visible in the creation of Royal Tenenbaum – a man who realizes he’s lived a life of falsehoods and emotional cruelty and knows he will never be able to make up for it. But, how can a man call himself a man if he doesn’t at least try?

Hackman’s own father abandoned him when he was just 13 years old. The actor lived with the memory of seeing his father wave at him from the car, and drive on, disappearing from his life once and for all. Knowing this, one might do the clever thing of looking at Royal as Hackman attempting to confront his own old man, trying to breathe some humanity into an irresponsible son of a bitch that scarred his life forever. That is, in essence, Gene Hackman’s acting legacy – giving a chance to every character he came across, good or bad, and hoping to find some truth at the end of this long and twisted tunnel we call life.