Blockbusters used to tell stories, often reflecting our worst fears about the world.

They were stories of men who faced adversity, injustice and corruption. Think Star Wars or Batman. Simple tales about the dangers of a world run by maniacs. Truth hidden in plain sight. Times continue to change and yet they stay the same, except that a lot of the dirt we managed to ignore before is now out there for all of us to see, at the touch of a single button. We live in a world that today’s blockbusters refuse to define. Too much money is at stake for producers to squander and risk having their reputation tarnished.

Once upon a time, though, blockbusters had balls. Even the ones we tended to dismiss as action-packed or epic, their message echoed and continues to echo to this day.

With the release of Gladiator II, I decided to revisit Ridley Scott’s original film from 2000 – the blockbuster that won Russell Crowe the Oscar and was crowned the year’s Best Picture. Over time, the film seemed to fall in people’s estimation with Scott himself being dissatisfied with the theatrical cut of the movie and offering a restored, extensive cut years later on Blu-ray. Crowe – who famously hated the script and never made any secret of his disdain for the campiness of the film’s storyline – would go on to give other better performances in films like A Beautiful Mind and Master and Commander (though his best performance, in my opinion, remains The Insider from 1999). Scott, too, would make better movies in the years that followed with Kingdom of Heaven, American Gangster and The Counselor on top of my personal list.

But upon revisiting the movie, though much of the criticism and skepticism regarding the film’s length and emotional beats may be still valid, one cannot help but be drawn to a blockbuster that is so concerned with what it means to be good and just in a world that is anything but those things. A blockbuster with a heart – a rarity in today’s cinema.

It is precisely this concern over the world’s morality that in retrospect makes Gladiator feel timeless. Even its most famous bits such as “What we do in life echoes in eternity” are glaring examples of a story that is focused on getting a message across – a simple yet vital message. The story of Maximus, decorated general of the Roman army turned gladiator on a revenge mission, is one that we have come to incorporate as an essential element of modern day pop culture. Hell, you’d be hard-pressed to find a hip-hop song of the 2000s that does not feature at least one quote from Maximus.

That is the power of blockbuster cinema – through its simplicity it brings people together, shining a light on communal experiences, on shared values that we take for granted. It is the reason why everyone came to love Harrison Ford in The Fugitive – here was a good man trying to set the record straight, trying his best to preserve his humanity in the face of injustice. Likewise, Gladiator is not so much about Maximus lending his combat skills to the cruel world of gladiators as it is about him finding a deeper purpose to life, beyond the glory of the battlefield.

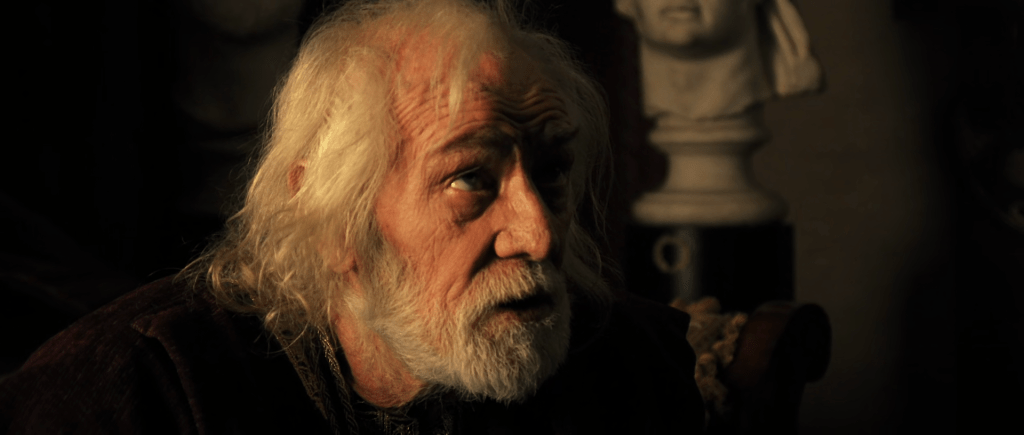

Gladiator is about shadows and dust, as spoken by the character of Proximo (a phenomenal Oliver Reed in his last ever performance, more about it later). Literally, the film shows the gradual progression, from the murky, foggy war-torn landscapes of Germania, to the dust of the Sahel and the gravel of the Colosseum’s pit. Scott – knowing that the script is hammy – has Crowe interact with the world around him. It is a palpable reality that Maximus inhabits. The ritual of grounding up some of the earth on which he is about to spill blood is just another way to emphasize Proximo’s point – we live and then, as if we never mattered to begin with, we’re gone. Shadows and dust. From dust to dust.

Even Marcus Aurelius (the legendary Richard Harris) is haunted by this matter. In the final days of the beloved Roman leader, the old man’s main preoccupation is memory. How will time look upon his reign? What will he be remembered for? “I brought the sword, nothing more,” he says. “Four years of peace out of twenty. And for what?” The great leader/philosopher is terrified of a life of regret, of a life without meaning. “What is Rome?” he asks. It appears that Rome is just a concept meant to justify the worst of humanity. To Maximus the general Rome is light, Rome is the reason he fights. Rome is his family. To Aurelius, however, Rome is nothing but a dream from the past. “When a man sees his end, he wants to know if there was purpose to his life.” Well, is there?

It is only in the face of death and hopelessness that Maximus understands Caesar’s sentiment. The deaths of his wife and son cause his world to shrink, to become bare and simple. All of a sudden his life is void of any meaning. All the killing he’s done is nothing but a stain – a life largely spent on battlefields all over Europe instead of at home, with his beloved, tending to his olive groves, his garden, his ponies.

It takes his loved ones to die for Maximus to wake up and understand the way Rome really works. “Rome is the mob,” as Senator Gracchus succinctly puts it. Rome does not stand for some higher ideal. Rome seduces and crushes its subjects, giving way to greed and abuse of power. Rome is no longer the place where good men can thrive and make a difference.

Maximus’ arch as gladiator, from the desolate, cheap arenas of Northern Africa to the grandeur of the Colosseum, is supposed to showcase the evolution of a loyal servant to Rome’s tyranny to a man whose imperative is to preserve his dignity as he stands up to evil, to the machine itself. By opposing Rome’s cruelty and opposing the forces that prey on his combat skills, turning him into a spectacle for the masses, he becomes the symbol of the Rome that Marcus Aurelius had envisioned all those years before.

Scott is not concerned with action, and on rewatching the movie it is apparent just how little the English director cared for the action sequences in this movie. The editing is clunky and often the cuts make no sense at all; just look at the amateurish sequence with the tigers in the Colosseum – you’re bound to spot about a dozen cuts that are so loosely strung together you can hardly make out what’s going on. The violence itself is often over the top and ridiculous, sign of a filmmaker who is in on the joke, whose real interest lies elsewhere.

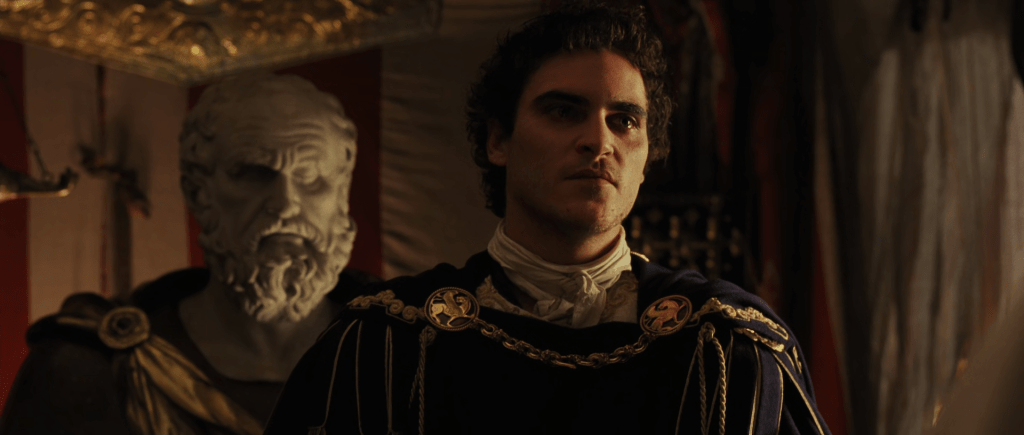

What Scott is concerned with the most is the theatricality of the film, the lavish spectacle of a morally broken world that pays to see people die in agony. He has Commodus pull out his tongue and grin in delight as a gladiator gets chopped in half; Joaquin Phoenix’s performance being emblematic of Rome’s depravity and moral decay. Scott films the action sequences by constantly switching to the mob of spectators, making them complicit in the atrocities they’re busy cheering for. “Conjure magic for them, and they will be distracted,” says Gracchus. “Take away their freedom, and they still will roar.”

The world that is Rome is the world we recognize in the news. It is the world we are part of. We the spectators, watching our leaders inflict pain and terror on innocent people. We the mob, applauding, grateful for the entertainment.

In all of this madness, being a good man is a tall task. Being a good man and having to kill hardly ever go hand in hand. But in the world of gladiators it is the only thing Maximus can do to preserve his sanity and, most importantly, his dignity.

“We are all dead men,” says Proximo. “Sadly we can’t choose how, but we can decide how we meet that end in order that we are remembered as men.” In this case Proximo means that one should not fear death, one should welcome it with heart and determination, like a proper gladiator. But we soon find out that Proximo is just as human as Maximus – he just forgot about it, that’s all.

Proximo is in many ways, together with Maximus, the beating heart of the film.

Reed’s performance (cut short due to the actor’s massive binge drinking which resulted in his death while filming was still on-going, forcing Scott to use a body double and computer effects for his final scenes in the finished movie) is immensely reflective of Crowe’s – the two match each other’s energy, showing the same humanity at the root of their characters’ being. Reed’s flamboyance make him the most compelling presence on screen, as he sells us the dreams of a broken man, of a once decent man who fell into the gladiator’s pit and never emerged from it. Proximo is the reminder of what can happen to a man when he is turned into a tool for the mob’s amusement. A man is bound to lose his ways. Gladiator is in large part a movie about Proximo’s redemption just as it is about Maximus’ revenge.

As a gladiator, Proximo lived thanks to the crowd’s adoration, mistaking it for respect and devotion. Compelled by the cheers and applause of 50,000 spectators, Proximo fooled himself into believing that the world was welcoming him as one of their own. It is only by witnessing Maximus’ indifference to the crowd that Proximo is reminded of a thing called dignity, of a moral compass which in his case has been broken for many years.

As slaver, Proximo has become his own worst enemy, the oppressor of his own past self. It is why we cannot help but root for his self-discovery as much as we root for Maximus’ journey. Proximo is the one who sees a difference in Maximus, and unlike the Senators or Lucilla, Commodus’ scheming sister and Maximus’ former lover, he is the only one honest enough to come to terms with his own involvement in the suffering of others. He helps Maximus not out of an obligation to serve a higher power, but out of a sense of long-lost dignity of a once good man.

For years the story of Maximus was seen as nothing more than an action spectacle, an underdog story of a man having to survive by any means necessary just to see his family’s killer die. People loved Gladiator because it was a romanticized fairy tale of a dead man beating the odds, going all out against the same people who once called him General and served him with devotion.

Today I think it is safe to say that Gladiator is more than that – it is the modern blockbuster par excellence, a film that truly understands how to entertain through a story that is timeless because sadly, like Rome, we’re stuck in a vicious cycle of corruption, greed and violence.

Like Proximo, we tend to forget about the importance of being good in this world. Being a good man is the most noble thing one can do when faced with injustice and oppression. Maximus is proof of that – proof that being loved is far greater than being feared. That men like Commodus are difficult to outnumber because hate and terror will always be more appealing than humility and heart. Evil will draw crowds and amuse those who crave distraction, regardless of the cost involved. But if we don’t try to be good, if we don’t make an attempt at preserving our own morality, then we risk being stuck in a self-inflicted state of limbo like Proximo, whipping ourselves for the benefit of those who rule the world, those who want us oblivious and easy to manipulate. Too many have fallen into the trap of fascism dictated by modern algorithms – like the thousands flocking the Colosseum, urging the gladiators to Kill! Kill! Kill! many of us have become blind to what is real, what is good, forgetting that a world of spectacle is a world lacking in morality. The importance of being a good man knows no bounds. And Maximus would agree with that.