Lately, I found myself thinking more and more about Alain Delon.

The French film star, who passed away on 18 August, has continued to haunt my thoughts and dreams over the course of the last few weeks. It got me thinking – what made Delon special? Far from a personal favorite, and yet his image, his face, his eyes, are deeply etched into my soul as a lover of cinema. How many times will I think of his cool fedora hat in Le Samurai? How could I forget his carefree swagger in Purple Noon? Or his juvenile playfulness in The Leopard? The dripping, sweaty looks he gives in La Piscine?

Something about Delon’s passing bothers me – it is perhaps the knowledge that a certain era of filmmaking has come to an end and the only thing left for us to do is to pick up the pieces, treasure them, preserve them. It is also the knowledge that Delon’s reputation as an actor will indeed be narrowed down to the thing that brough him universal acclaim in the first place – his looks.

But, I want to use this opportunity to highlight the man’s acting. More specifically, I want to look at one of his lesser known films and yet one of the films he was proudest of (as often happens with actors, what they consider their best work rarely results in box office success, just look at Jack Nicholson and his love for Antonioni’s The Passenger) – and for good reason. Valerio Zurlini’s hugely underseen Indian Summer (a terrible title considered the original Italian one translates to The First Quiet Night) is easily among Delon’s best performances. I would even argue it is his best because there is nothing about it that screams movie star.

In fact, Zurlini’s film is one of the most downbeat, miserable films of the 1970s – certainly of Italian cinema. At the time, Italy was going through one of its most turbulent periods with fascists and communists clashing on a daily basis, engaging in mass murder, kidnappings and extortion in the name of political ideals. The worst thing you could do at the time is be indifferent to the plight of either faction. And that’s exactly what Delon’s character does – he acts indifferent to the world around him, unbothered and disinterested in the direction society is heading in.

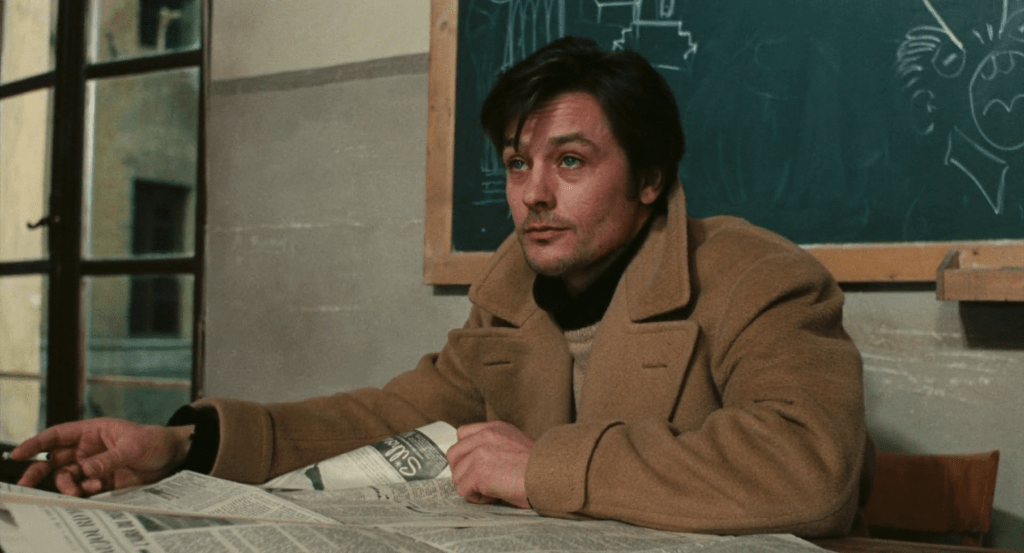

Delon plays Daniele Dominici, a high school professor and poet, who finds himself on a temporary teaching assignment in the drab, foggy seaside town that is Rimini. It’s 1972 and Delon no longer looks the part of a young, innocent starlet. He’s got deep eye bags, a three-day stubble and unkempt hair. There is no luscious make-up. No shining teeth. It is all authentic Delon, probably going through one of his own heartbreaks, depressed and disillusioned with the way his career was transitioning into uncharted territory – no longer deemed the new kid on the block, he was now forced to battle for the roles that once upon a time may have gone to the likes of Lino Ventura or Yves Montand.

“I am here to explain why one of Petrarca’s verses is lovely, and I think I can do it well,” Delon’s professor Dominici tells the classroom on his first day at the school. “All the rest bores me. Red or black, you are all the same. The black ones are more stupid.” Dominici says it without emphasis: it is all one flat stream of words that he utters with a cigarette dangling from his lips – a habit we’ll come to expect from him as he spends the rest of the movie perpetually toying around with cigarette butts. Cigarettes – the act of lighting them, giving life to an inanimate object – is perhaps the only certainty left in Dominici’s otherwise empty life.

Dominici is in a loveless marriage. His wife spends most of her time at home, crying, pondering suicide and writing letters to lovers – a timid attempt at catching her husband’s attention. “It will pass,” he tells her when confronted with her tears. “Everything passes,” he says, as in everything – including love. “Do you have regrets?” she asks him. “Too much luxury. I couldn’t afford it,” he replies dryly.

The two share a bond that is solely constructed on the foundations of a fragile past. “We’re together not even out of habit but out of desperation,” as Dominici puts it. For Dominici, and perhaps for Delon at the time too (this is almost a decade after his break-up with Romy Schneider whom he considered the greatest love of his life), love is nothing but a burden and one that he is not willing to carry anymore.

The professor has gotten himself to a point where he does not consider the future but simply drifts like a nomad in the shallowness of the present moment. When he’s not wallowing in melancholy, he plays card games and attends house parties composed of people as bored stiff as him.

In Zurlini’s film, Rimini has nothing to do with the romantic setting of Fellini’s Amarcord – here it is presented as a lonely, empty town with grey streets, filthy beaches and nothing to do besides playing the bingo and aspiring to move elsewhere. Those who stay are trapped within the confines of a city that has no beginning and no end. Perhaps that is why Dominici accepted the assignment despite his clear lack of interest in his profession – he is unable to inhabit a more challenging reality, a reality that may remind him of his past and actually elicit some feelings in him. In a way, Dominici finally allows Delon to play a character who is muted; whose traits cannot be accurately summarized with a cool-looking poster, tapping into his former bad boy persona. Dominici is too complex for that, too hopeless and disturbed. His partnership with his wife lasts only because they’re equally as miserable and thus she poses no threat to his permanent melancholy.

The awakening happens when Dominici meets and confronts one of his students, Vanina Abati. After a preliminary interrogation in the classroom, the professor realizes that this girl is different. When the class is assigned a choice between a literary essay and a personal introduction, Vanina is the only one who chooses to write about purity and sin in Alessandro Manzoni’s work. This refusal to open up, unlike the rest of her classmates, and let others into her life, sparks Dominici’s interest in her.

In Vanina, Dominici sees the first signs of his own rebellion against the world. He recognizes his own reflection in her sad, disappointed eyes. Her monotone voice reminiscent of his own when compelled to answer questions. But more than that, he feels challenged by her. Vanina does not give him an easy time – for Vanina nothing is easy, everything comes at a price, especially when we talk about secrets; every life is filled with them, thus putting us at risk, and at the mercy of others’ inquiring stare.

He is troubled by her determination to avoid giving herself up; and he’s even more troubled when he learns that she hangs out with a rich asshole boyfriend despite knowing fully well that he constantly cheats on her. “The pain you have inside…I can’t stand your helpless melancholy,” Dominici finally says to her. It is an admission of kinship, of understanding between two souls who had forgotten what it feels like to relate to someone else, to have an interest in another person’s fate.

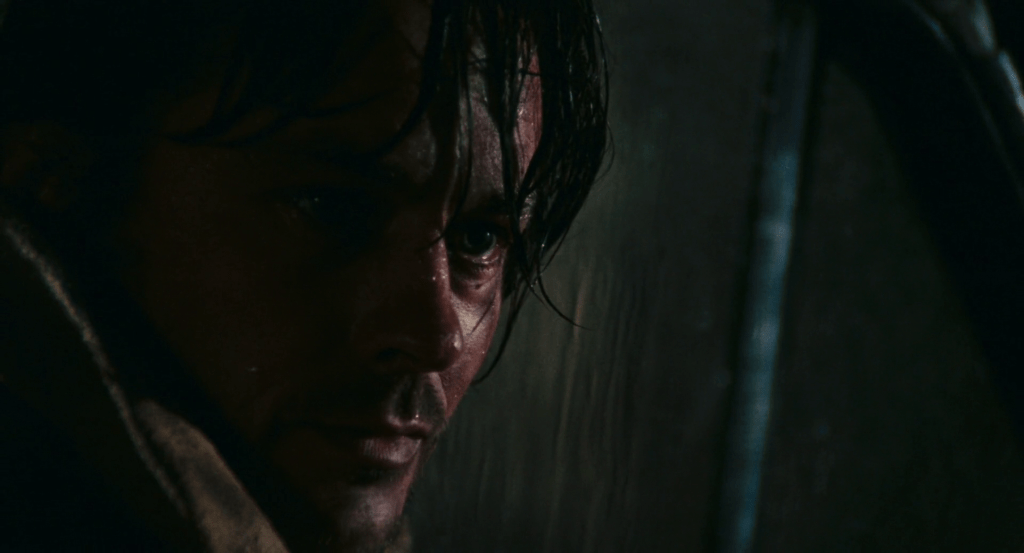

The wonderful thing about Zurlini’s film is that it does not stop there. It does not satisfy itself with this simplistic outcome – the innocent friendship between a teacher and his student. And it doesn’t resolve in the way other films of the kind in those years did, films about a man’s infatuation with a woman, say Rohmer’s Love in the Afternoon, about sexual awakenings in middle age and the shocking discrepancy between generations. No, Zurlini’s film goes in a whole different direction. And so does Delon’s performance. He plays Dominici as if he were playing a character who’s been dead for a long time. And there is no coming back from it. His interest in Vanina, his eventual process of falling in love with her does not show a man capable of being happy. The best outcome Dominici can hope for is to minimize the pain of his own existence. But whatever took place before, will not simply fade away, and that applies to Vanina, too.

The scene of Dominici watching Vanina dance at a party with her boyfriend, slowly sinking her head into her boyfriend’s shoulder, is – in my opinion – some of Delon’s best acting. Stone-faced, he shows the professor experiencing what can only be profound love for a person who is clearly as tormented as him. And yet, in this situation he cannot do anything about it. He sits on a couch, overlooking the dance floor, Ornella Vanoni’s love ballad blasting from the speaker as Vanina raises her eyes and sees him watching her. The two trade looks. But while Vanina can hide from his gaze, Delon’s Dominici has to sit there and take it in like it’s nothing. He’s on display, people are watching, and Delon has the tall task of making us understand that Dominici, for what it’s worth, is completely in love with this woman whom he cannot have. This man – whom we considered dead – is indeed capable of feeling, of wanting, of longing for.

Despite the cruelty and moral turpitude of the world he inhabits, Delon does not act as an outsider the same way he did when playing a contract killer in Le Samurai where he had to dodge and avoid all interactions with others.

In Zurlini’s film Delon is still able to evoke the sense that Dominici has already gotten a taste of this cruelty and abandon, he’s had his fair share of it, perhaps even contributing to it in his own way, in some distant realm of the past which we now have no access to. He willingly goes to places crowded with the same kind of people that he says he despises. He surrounds himself with the vilest, most insecure men, all guilty of treating women like dirt, and doesn’t make it a secret when he befriends one of them, nicknamed Spider (played by a very young Giancarlo Giannini), and mostly uses him to run errands for him.

There is a complete lack of ‘holier than thou’ in Delon’s creation of Dominici. You almost feel that the actor made it a point to not come off sympathetic in spite of the circumstances that his character is dealing with. There is not a single moment where Dominici feels false as a character – his choices, his actions remain mostly unclear to us, sometimes even erratic and violent, like when he decides to fuck his wife out of sheer rage and helplessness, both of them wanting to feel something – anything – for the sake of their dissipating marriage. It is an upsetting, mean scene involving two people wrestling with themselves more than with each other. It is a display of simultaneous emotional cruelty and desperation the likes of which Delon was not known for. He’d always been the pretty boy or the cold, calculating gentleman, but never a mean son of a bitch of this caliber. But Dominici’s meanness is clearly motivated by something and that is what keeps it from being perceived as just plainly nihilistic. The hopeless professor is the way he is because something’s gnawing at him, the same way Vanina is the way she is because of the tormented past that continues to haunt her.

The meanness is, however, at odds with Dominici’s sensitivity and love for poetry. These are the domains that speak to his heart. He appears just as amazed at the sight of a Renaissance painting as he is when walking through the halls of a decrepit, abandoned country house that used to belong to friends of his family. Despite his perpetual sense of ennui, Delon’s character is capable of wonder and passion. Perhaps he’d rather live without it, as he knows that his life will never be able to reflect such beauty, such long-lasting vitality. “She is aware but not happy,” Dominici notes while looking at the Madonna del Parto painting by Piero della Francesca in Monterchi. “Maybe she senses that the mysterious life growing inside of her will end up on a Roman cross, like that of a wrongdoer.” He says this not only in awe of the painting, but more so in awe of the Virgin Mary’s courage in the face of her tragic predicament. The world cannot be hopeless for as long as such courage exists. Dominici knows this, and perhaps that is why he hides out in Rimini – out of shame for his cowardice.

It would have been to simple to ignore Delon’s dark side. The movie doesn’t commit this mistake. Instead, it embraces Delon’s contradictory nature. The actor’s long history of controversy shows a man at odds with his profession. On the one hand he was drawn to the lyrical world of movies – he was undoubtedly responsible for contributing to some of cinema’s greatest masterpieces; while on the other hand he also appeared susceptible to the lifestyle of gangsters and the politics of tyrants. However, it is also why Domenico Dominici in The Indian Summer is such a special part in the actor’s extensive film career. It is in this small, underseen movie that Delon got to channel all sides of himself: the violence, the poetry and the fear of loving again. I predict that Delon’s passing will not sit right with me for quite some time- his death represents the end of an era, the end of a world compromised of gods of cinema such as Luchino Visconti, Michelangelo Antonioni, Monica Vitti, Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jean Pierre-Melville, and many more, the likes of which we will never see again.