“What came first? The music or the misery? Did I listen to pop music because I was miserable? Or was I miserable because I listened to pop music?” says Rob Gordon in the opening scene of High Fidelity.

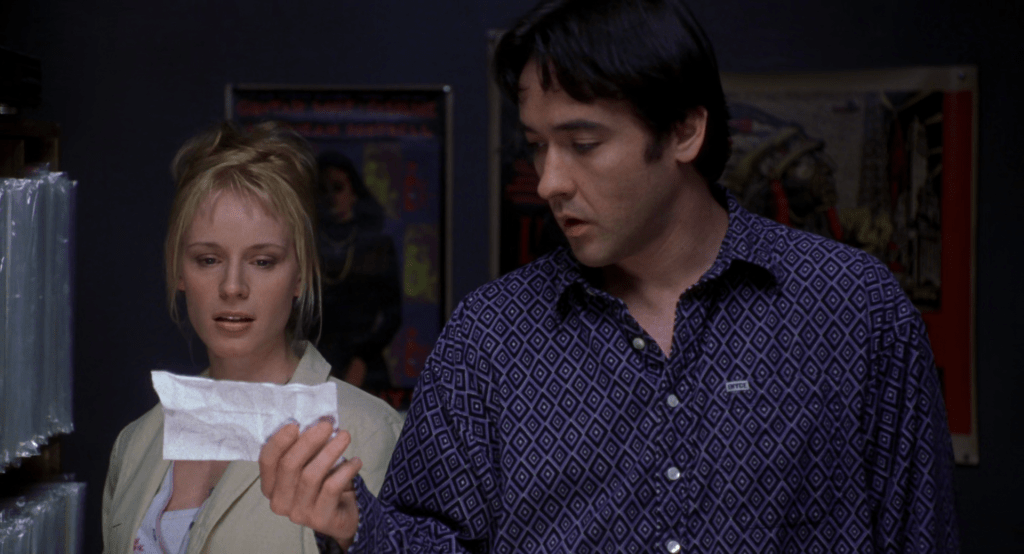

John Cusack plays Rob in Stephen Frears’ wonderful adaptation of Nick Hornby’s iconic book. It is this opening line that in of itself conveys not only the main theme of the movie – that of the intrinsic role of music in our lives – but also the self-centered nature of our asshole protagonist. Rob is, for better or worse, a fucking asshole (as coined by the character of Liz, played by Cusack’s sister – Joan). He’s also a great example of a seemingly unsympathetic leading character that somehow is able to swindle the audience into tolerating his endlessly fascinating (and superficial) observations on women, music and how the two go together. The film is a glorious lightning in a bottle of a by-gone, pre-9/11 era of filmmaking, of characters talking the talk and walking the walk, of original stories effortlessly weaving low-stakes situations with real, palpable emotions. At its core, despite not taking itself too seriously, High Fidelity is about acknowledging others around us – and it does so by tapping into its unapologetic, snobbish asshole of a protagonist.

At a time when movies that treated similar themes preferred to delve into the romantic or melodramatic, High Fidelity came and reaffirmed its place as an original take on the toxicity of certain representatives of the male population and their twisted attempts at reckoning with the past.

Because that is what Rob Gordon – music aficionado and grumpy record store owner – sets out to accomplish, supposedly – he asks himself, ‘Why am I doomed to fail? Doomed to be lonely and miserable?’ Rob is a man who passes himself off as a regular Joe, but deep down there is a willingness to put himself above the rest of the crowd of losers he sees on every corner. The choice to film this movie in Chicago instead of London, the novel’s original setting, further serves to highlight this disparity and simultaneous synchronicity between Rob and his environment. Rob walks the hard-looking, steely streets of Chicago as if he owned the damn place. And the movie dares to follow him along – it does not shy away from embracing his confessions.

Because films used to trust us. Some still do. They treat their audience like adults – they drop little hints, confident the viewer will pick them up like a trail of bread crumbs and make sense of them on his own terms. High Fidelity relies on the audience to see through Rob’s confessions. Here is a man who is seemingly ready to spill his life, his guts, right in front of us. Here is a man who’s got nothing to lose anymore, a man who’s willing to come clean, right? Wrong.

The story of Rob Gordon is a smoke screen for the countless people he’s come across in his life and dismissed or who dismissed him for reasons apparently unbeknownst to him. Rob’s plea for help is a fitting disguise for the kind of man Cusack’s character is mocking, the kind of dude who will always, no matter what, sell himself as the victim of a situation that involves the bare amount of accountability. And we – the audience – must connect the dots and not fall into the trap that would imply the film endorsing Rob’s attitude.

As revealed in the film’s opening line, Rob paints the canvas of his life through music as a motivator and guardian angel watching over him. Music for Rob is also almost like a weapon meant to express his veiled superiority over others. It is his way of seeing the world, his own life. For God’s sake, he even starts rearranging his record collection in autobiographical order. “I can tell you how I got from Deep Purple to Howlin’ Wolf in just 25 moods. And, if I want to find the song “Landslide” by Fleetwood Mac, I have to remember that I bought it for someone in the Fall of 1983 pile – but, didn’t give it to them for personal reasons.”

Rob explains his life and the decisions he made through the music that inspired him – but is the inspiration real or just an additional cloak? Hell, the only reason he doesn’t give us a lowdown on his sexual endeavors is because Charlie Rich taught him to keep such things on the hush-hush with his song, Behind Closed Doors. Instead, he muses with hard-edged finality, as if he were quoting Ernest Hemingway, “I can say we had a good time. I can say that. Marie is a terrific woman.”

But Rob’s musings don’t really translate into anything worthwhile because he’s still trapped within the confines of his own superficiality. Cusack and Frears understand Hornby’s material to such a degree that they choose to stage the entire movie through the act of Rob breaking the fourth wall and speaking directly to the audience. By now, High Fidelity has grown into the cult movie that it is today mainly thanks to this brilliant technique that gets at the heart of Hornby’s book and presents Rob for who he is: a self-absorbed asshole in need of attention.

Yet, Cusack never loses us despite the worst secrets about Rob and his wrongdoings as a partner and lover eventually come to surface. His gaze, his sarcastic remarks and self-pity are our way into the psyche of this douchebag who fails to acknowledge his role in the story he’s telling. Cusack’s remarkable sense of irony and charm turn Rob into a – for better or worse – relatable asshole; as in Rob is plagued by the same worries and frustrations that each one of us, in spite of the best of intentions, may have experienced at some point in life.

Rob’s attempts at masking his own insecurity by pointing fingers left and right only result in more selfish acts of emotional cruelty. He always seems to rearrange everyone’s story: when his long-time girlfriend, Laura, spills the beans about Rob’s infidelity, the consequences of it on her short-lived pregnancy and their eventual break-up, Rob – like a good chunk of the male population would do in this situation – falls back on a series of panicked justifications. In his mind, everything is aimed at him, the way it was aimed at infamous American gangster John Dillinger before he was shot and killed by the FBI. “John Dillinger was killed behind that theater in a hale of FBI gunfire. And do you know who tipped them off? His fucking girlfriend,” Rob tells us in disbelief. “All he wanted to do was go to the movies.”

Perhaps the most telling aspect of the kind of person Rob’s character is meant to depict is his golden rule of making up Top 5 lists for literally anything that holds any kind of meaning in his life. Whether it’s his all-time favorite records or all-time favorite things about what make Laura such a great girlfriend, Rob cannot help himself but categorize life in a well-constructed box dictated by a series of criteria that he’s got sole access to. He processes his life, his memories through this weird magnifying glass meant to narrow the attributes of an experience or a person down to 5 identifiable elements. Rob is trapped and he doesn’t know it. And it all starts with the list of his Top 5 break-ups and his surface-level pursuit of absolution – the pursuit of happiness minus the accountability. “Once you talk to them, they’d feel good, maybe. But you’ll feel better,” a vision of Bruce Springsteen tells Rob as he considers visiting his former girlfriends and walking them down memory lane. “I’d feel clean and calm,” says Rob dreamily. It’s all about Rob, isn’t it?

For Rob, the greatest expression of feelings is represented by the act of compiling a mixtape for someone. “The making of a good compilation tape is a very subtle art. Many do’s and don’ts,” he tells us. But for the most part, tapes only serve Rob to highlight his musical taste and knowledge. Show the world how cool and hip he is. He explains to us the art of starting off a mixtape with a few really good songs just to bring it down a notch in the middle in order not to burn out your best stack of cards. It is all but a demonstration of love and more of a masturbatory self-defense mechanism as if to say, “Here, this is me. This is what I have to offer.” For Rob, the other person doesn’t enter the equation. Or perhaps, that is the revelation in a movie that is incredibly funny despite being populated by awful characters; that, like in life, the realization that other people matter, and the ones that we consider really special are the ones we put ahead of our own interests, is the greatest revelation a person can have. A person like Rob – who walks the streets seeing not people, but shadows; he calls them ‘visions’- until the day comes and he realizes that visions don’t work in the long run. It’s about the person sitting in front of you. The one whose taste you should consider before making them a tape.

Finally, it would be impossible to write about High Fidelity and not consider the way it weaves it soundtrack with the story the film is telling. Frears – along with Cusack, whose input in the film goes far beyond his starring role as an actor – constructs vignettes that are primarily motivated by the soundtrack. Springsteen’s famous ballad, The River, is used to elicit the melodramatic nature of Rob’s brief affair with girlfriend number 4 on the list, Sarah, and the genuine desperation those two characters may have felt at a time that is now a faded memory. And Dylan’s Most of the Time comes at a crucial stage in the movie where Rob is starting to wake up from his emotional and moral slumber – it is a beautiful moment of reckoning with one own’s guilt and the unavoidable nature of it. And perhaps the most emblematic piece of music used in the film is Marvin Gaye’s Let’s Get it On and Jack Black’s rendition of it: it is a singular moment where everyone – Rob above all – expects disaster and is instead confronted with a beautiful moment of sensuality and feeling. At the heart of it, the music in High Fidelity is able to overcome Rob’s bullshit and gives us a true glimpse into the human side of this massive asshole we’re hanging out with. An asshole that we seem to tolerate. In High Fidelity music is the truth; truth distilled in a series of notes, impossible to tame within a reductive Top 5 list.