One of the founding genres of cinema, like the Musical, continues to be termed “a dying breed,” yet the Western is still to this day a powerful reminder of the lasting effects of urbanization, greed and class struggle. Filmmakers nowadays prefer to steer clear from the genre as few people seem to be interested in cowboys and gunslingers anymore. It’s a shame because one of the best films of the century, Hell or High Water, happens to be a Western and happens to possess a timeless quality in the same vein as some of its more famous predecessors like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence, The Magnificent Seven and Rio Bravo. By diving into the conventions of the genre and ultimately subverting them, Hell or High Water presents a new world, our world – a world of post-recession, of folks struggling to make ends meet and of generations scarred by a rigged system and a steadily declining economy.

The film tells the story of two brothers, Toby (Chris Pine) and Tanner (Ben Foster) Howard, who go on a robbing spree of local banks in West Texas in order to get back their family home. The man who goes after them is Marcus Hamilton (a phenomenal Jeff Bridges in an Oscar-nominated performance), a worn out veteran Sheriff who, with each passing day, is edging closer to retirement. Classic, isn’t it? The film seems to be about good guys chasing bad guys until the lines become blurred and we realize that circumstances have twisted our original understanding of our characters. Gone are the days of despicable bandits in the form of Lee Marvin or Eli Wallach. Characters without morals and remorse. The real bandits in Hell or High Water are the banks our protagonists are busy robbing. It’s a David versus Goliath story where the two brothers take it upon themselves to set the record straight and get even with the system that fucked with them for generations on end. “I’ve been poor my whole life, like a disease passing from generation to generation. But not my boys, not anymore,” says Toby, determined to change the fate of his heir.

Set in present-day Texas but made to look like the great movies of New Hollywood of the 1970s, Hell or High Water carries a mournful tone to it. The music of Nick Cave and Warren Ellis, sparsely scattered across the film’s tight 100-minute run time, serves to underline the somber reality our protagonists operate in. West Texas looks run down, populated by unfortunate souls who failed to escape the drought – both physical and financial – and whose biggest claim to fame could be winning the local lottery or earning a hefty tip at the burger joint on a Sunday night.

While in pursuit of the two suspects, Hamilton and his half Mexican, half Native American partner, Alberto, come across a large herd of cattle being run away by a group of cowboys from the impending brush fire, typical of the dry season. Hamilton offers to help them, but one of the cowboys responds, “Ought to let it just turn me to ashes, put me out of my misery... 21st century, I’m racing a fire to the river with a herd of cattle. And I wonder why my kids won’t do this shit for a living..” We are witnessing the passage of ghosts, men whose existence has become a burden to their own sons and daughters.

But more than anything else, Hell or High Water continues the tradition of Westerns about men haunted by their own past. Like Robert Vaughan’s gun-for-hire in The Magnificent Seven – who halfway through the movie admits to himself that he’s scared shitless and his whole life is a lie – or Dean Martin’s drunken ‘Dude’ in Rio Bravo – whose once steady hand is now plagued by the regular shakes of an alcoholic – Jeff Bridges’ Sheriff Hamilton is a man grieving the passing of his wife, set on chasing the bad guys until the end of his days, deep down wishing that somebody would do him the ultimate favor and put him out of his misery so that he can die a hero and be buried one. He can’t sleep, he rarely gets anything to eat. His profession is just that: a job, a procedure of going through the motions that provides him with some thrills from time to time, enough to get by and avoid spending too much time in his own head.

While his partner sleeps comfortably in a warm motel room, Hamilton sits outside the room, out in the parking lot, wrapped in a poncho, staring at the clouded night sky before him. He doesn’t know that the man he’s chasing, Chris Pine’s Toby, is spending his days pondering the same things as him, haunted by similar demons.

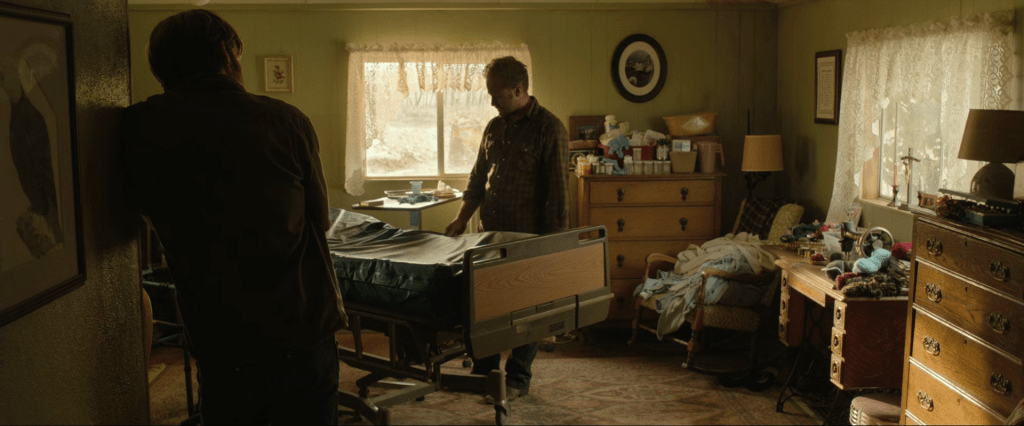

Deep down, Toby is scared of the path life put him on. The path of crime, of robberies and violence. Unlike his brother Tanner who did hard time in jail and has a taste for breaking the law, Toby is acting against his own nature for the sake of his children. He wants to gift them a brighter future because he’s tired of seeing folks drown in misery and sorrow, his own kin and blood.

Poverty plays a large role in the film. It is the main threat and motivation in the lives of the characters that populate it. Even the waitress who Toby tips refuses to hand her tip as evidence to Sheriff Hamilton “because that’s half my mortgage and the money I use to keep a roof over my daughter’s head.” Every penny counts. Every penny makes a difference. This may not be a country for old men, but it’s not a country for younger people either. Everyone’s doomed. Except the banks.

The greatest strength of Hell or High Water is its modesty – reflected in the no-nonsense run-time – and its sharp, observant eye which captures a place without necessarily pinning it to a specific period in time. The movie refuses to hint at historical or sociopolitical events which may help us establish a more accurate timeline. As a result, the film’s message becomes timeless and universal. Its depiction of people struggling in the face of corporate greed is one we know from some of the greatest movies of all time like Bicycle Thieves and The Grapes of Wrath. Suffering is, after all, timeless. Suffering is impossible to stop and pin down. In cinema, we have been blessed with characters willing to sacrifice themselves to minimize the suffering and struggle of their loved ones. Similarly, Toby and Tanner are ready to put everything on the line despite a traumatic childhood and growing up almost tore them apart. For me, the perseverance displayed in Hell or High Water is what I look for the most in movies. The strength of spirit, the eagerness to beat the odds. After all, it’s what we dream of – a vision of a more comfortable life, of a safe and secure existence for our sons and daughters. “The things we do for our kids, huh?” observes Sheriff Hamilton after confronting Toby for the first time. It’s then and there that Hamilton realizes that most men are not greedy or violent by nature. The bad guys he chased most of his life were probably driven to the extreme by the circumstances they longed to escape since the day they were born.

The last great Western of the 21st century uses universal and timeless concerns, pitting similar-minded characters against each other. The seemingly tired genre – the one Hollywood is now eager to abandon – is able to tell the story of generational sacrifice and persistence. Hell or High Water understands its roots and knows that in order to get to the truth you have to dig deep and return to a time and place that most of us knew at some point. It’s there, in the darkness that is poverty, that we often find the greatest displays of compassion and strength. It’s there that someone like Sheriff Hamilton comes to realize that life is not black and white. We may like to believe it is, but the sooner we learn to accept its different variations, the better it will be for us and the generations that will follow.