In a filmography that spans almost thirty years (since his debut with Bottle Rocket in 1996) and a style that has been labelled as ‘quirky,’ ‘operatic’ and ‘artificial,’ the movies of Wes Anderson have become a sort of staple in our cinematic landscape. Each release has grown into an event involving audiences of all ages, tapping into the sensibilities of viewers not because of its perfectly symmetrical compositions and exquisitely sharp lighting, but because Anderson’s films are perhaps the closest we can get to dreaming with our eyes open, in a similar vein to audiences swarming theaters to see the early films of Walt Disney in the 1930s and 40s and marveling at the explosion of ideas on the screen before them.

Anderson’s latest – Asteroid City – is a continuation of the director’s most persistent (and misunderstood) theme of grief; a theme so heavy and invasive on the surface, which in Anderson’s hands becomes a gentle melody, lulling us into a state of peaceful, soothing trance.

Asteroid City – like a lot of Anderson’s recent films including Grand Budapest Hotel and The French Dispatch – is a period piece telling a story within the story. It is a film that is borne out of a seemingly long-gone past that – as we’re bound to find out – is still very much reflective of our own times. The primary story takes place within a stage play written by a tormented playwright. Every now and then, Anderson reveals what goes on behind the scenes of the play’s production, including the process of finding truth within the written text.

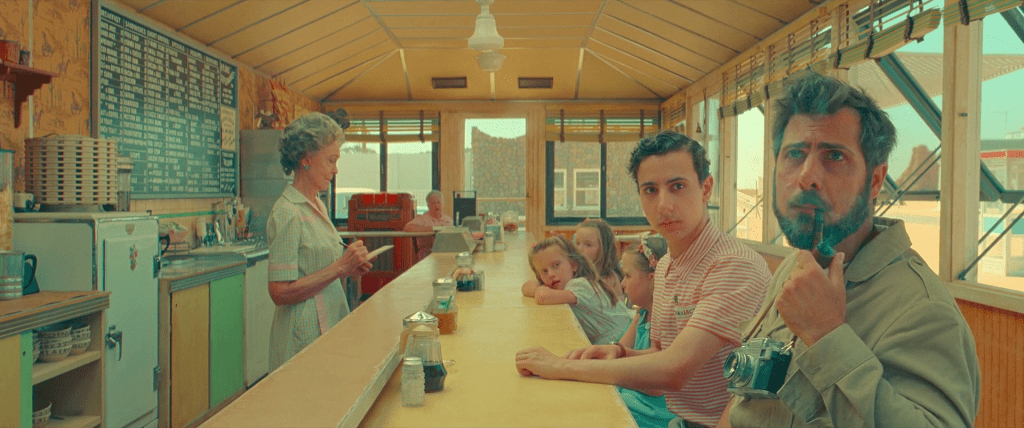

The play concerns the story of the titular Asteroid City, a remote town in the middle of the desert, not too far from where they’re testing the atomic bomb. The time is circa 1955. Anderson once again stages the action within a singular, three-dimensional setting, bringing a vast cast of characters to life, primarily led by Augie Steenbeck (played by Jason Schwartzmann, an Anderson regular since the days of Rushmore): an award-winning war photographer and father of four. The family is attending Asteroid City’s Junior Stargazer/Space Cadet convention during which Augie’s eldest, Woodrow, is supposed to receive a recognition for his work in the field of ‘astronomical imaging’.

Meanwhile, Augie has the impossible duty to break the news to his children that their mother passed a few weeks ago. Augie remarks several times he doesn’t believe in God nor does he believe in a painless resolve. “Time doesn’t heal all wounds. No. Maybe it can be a band-aid,” he tells his children, although he knows his youngest ones have no real sense of time. It is a foreign concept to them, and thus, what is their concept of death and consequently the grief that follows? Is there anyone that is equipped to deal with grief? These are questions that arise within the opening twenty minutes of Asteroid City as they do in The Life Aquatic of Steve Zissou, The Darjeeling Limited and Grand Budapest Hotel, among many others in Anderson’s oeuvre. It is this relentless, almost shameless admission of powerlessness in the face of the enormity of death that makes Anderson’s trademark cartoon settings subvert our expectations. His stories are – beneath the layers of caricature, musical numbers and quotable lines – stories of human perseverance.

But Augie is not the only one wrestling with difficult circumstances. Hollywood star Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson) is in town for the same reason as Augie – her daughter is accepting a prize at the Stargazer convention. Midge sports dark sunglasses as she is trying to get a grasp on a new character she’s supposed to be playing in a few weeks. Beneath the sunglasses, she wears grease paint, pretending to have a black eye. “How does your character get a black eye?” asks Augie. “She doesn’t,” explains Midge. “It’s on the inside.”

Midge comes from a history of domestic violence; she is on her third marriage, her film career is supposedly fading with audiences failing to notice her wide-ranging talent, and now all she’s got is her daughter and what may very well be her last, meaningful part to play. It is in Augie that she finds the same sense of restlessness and doom. “I think I know who we are: two catastrophically wounded people who don’t express the depths of their pain because we don’t want to. That’s our connection,” she says.

In his writing, Anderson always had a knack for this kind of immediate, lighting bolt of emotions interjected into scenes of otherworldly mundanity; characters exchange powerful remarks in utter deadpan sincerity and then go on with their lives, almost as if what they had just said or done belonged to a different reality, a different time.

In Asteroid City everything takes on a surreal appearance. After all, it’s a story within a story, and the story stems from the twisted mind of a boozing playwright (played by Edward Norton). In the play, the question that afflicts each of the dozens of characters is: Why? And that question becomes even more resounding once an alien comes to visit Asteroid City and borrows the titular asteroid. Panic ensues. A state quarantine and lockdown is inflicted on the inhabitants of the town and its recent visitors. Our characters must – like in a playwright’s wet dream – confront their own demons within the confines of an extreme setting. For Anderson, this is a chance to reveal more layers of painful truth.

As mentioned earlier, quarantine pushes our characters – in typical Wes Anderson fashion – to confront each other out in the open. No more hiding. Parents soon realize what their children are capable of to get a second of their attention. One of the parents attending the convention, JJ Kellogg (played by Liev Schreiber), asks his son – another science whiz kid – why does he continue to ask everyone around him to keep daring him to perform dangerous stunts. “I don’t know. Maybe it’s because I’m afraid otherwise nobody will notice my existence in the universe,” blurts out JJ’s son.

Similarly, Stanley Zak (played by Tom Hanks) finally agrees to bury the ashes of his daughter – Augie’s wife – in Asteroid City’s sandy earth, accepting the fact that he cannot control everything, much less the wishes of his grand-daughters who beg him to let their mother rest in the spot of their choice.

And yet, Anderson never really resolves the mystery or pain weighing on the shoulders of our characters. That would be too easy. Despite the playful tone of his movies and the seemingly cheerful endings to most of them, Anderson is well aware that certain things we’re bound to carry with us until the end of our days. It is through the occasional behind-the-scenes look at the production of the play in Asteroid City that we get a glimpse of the torment not only of the playwright, but the actors as well. It is the actor playing Augie who exits the soundstage and confronts the director, begging him for more insight on his character. “I still don’t understand the play,” he says, to which the the director (played by Adrien Brody) replies, “Doesn’t matter. Just keep telling the story.”

Anderson’s unflinching confidence in his own voice and means is what continues to set him apart from most of his contemporaries. He is a storyteller that rises above whatever it is that critics and audiences like to throw at him, whether it is praise or insults and mockery, and taps into real, heart-breaking truths by doing what a storyteller should always do: tell the story. No more, no less. Because it is through his stories of broken families, grieving sons and daughters, failed marriages and estranged children that Anderson is able to provide us with a canvas filled with riches. It is up to us to find meaning in his stories. We get to have the final say, he just keeps telling the story.