The recent passing of Silvio Berlusconi shocked an entire nation. A nation that went into mourning with people pouring into the city center of Milan, standing in front of the Duomo with banners and posters displaying messages of love and devotion to the former Prime Minister. For Italians, ‘Silvio’ – as we like to call him – was the representation of an unachievable dream, a blurred vision of what people from this country could aspire to if their parents had left them a fortune to build their own empire. For many Italians, Berlusconi was God. His word was sacred. His acts of depravity and debauchery were mostly admired and always justified. He made ‘bunga, bunga’ a way of life – a way of laughing in the face of morality and justice.

Italian filmmaker Paolo Sorrentino tackled Berlusconi’s legacy in his underrated film Loro which in Italy was released in two parts, whereas the rest of the world only got one comprehensive cut starring Tony Servillo as Berlusconi. At festivals, the film was met with tepid reception. After all, it was no The Great Beauty. In Italy, on the other hand, it was despised. Sorrentino’s movie had touched a nerve, ridiculing its audience and the man who’d been the face of the country for the last 30 years.

Berlusconi’s reign starts with the people. Loro – the film’s title – literally translates to ‘them’ as in the people who made it all possible. And Sorrentino’s film does exactly that, placing most of the initial focus on the outsiders looking in, with Berlusconi’s aura looming over them.

Sorrentino introduces to us a cast of supporting characters that are just as vital to the film as Silvio himself. Young Sergio Morra (played by Riccardo Scamarcio) – a small-time crook who wants to make it big on the political stage. In his free time he bribes local officials, fixing them up with Albanian prostitutes (one of them even has a tattoo of Berlusconi’s face on her buttocks). Sergio’s wife is also in on the fix and will do anything in her power for her husband to be noticed by Berlusconi’s entourage.

Then there is Kira (played by Kasia Smutniak) – an Albanian immigrant who spent the past ten years chasing after Berlusconi. She’s his mascot, tragically in love with him, terrified at the idea of being ultimately rejected for someone younger.

Berlusconi’s wife, Veronica (played by Elena Sofia Ricci) is also a pivotal presence. She’s our reminder of who Berlusconi was and his ability to lure even the most beautiful woman in the world. In Loro, Veronica is one of the few characters who’s managed to figure out what Silvio’s trick is. She’s read through his bullshit, but it may be too late for both of them.

The rest of the world in Loro is pure noise because it is only through noise that a construction developer and cruise ship crooner could have gone on to become a world leader and certified billionaire. Loro – or them – are the reason for Silvio’s rise. Millions of heads nodding in approval of every single world, every single joke. Long lines of half-naked girls waiting to be summoned at his villa in Sardinia. Actors, senators and footballers willing to risk it all just for Berlusconi’s attention.

The first thirty to forty minutes of Loro are only composed of Sergio Morra and his gang of depraved lunatics desperately trying to find their way into Berlusconi’s charms. They claw their way through drugs and alcohol, through senators and other yes-men seeking Silvio’s ultimate approval. “This party in Sardinia will be the best investment of your life,” Kira tells Sergio. “He will notice you and your parade of whores and he’ll show his gratitude.” In Silvio’s Italy, a parade of whores is enough to open the gates to the nation.

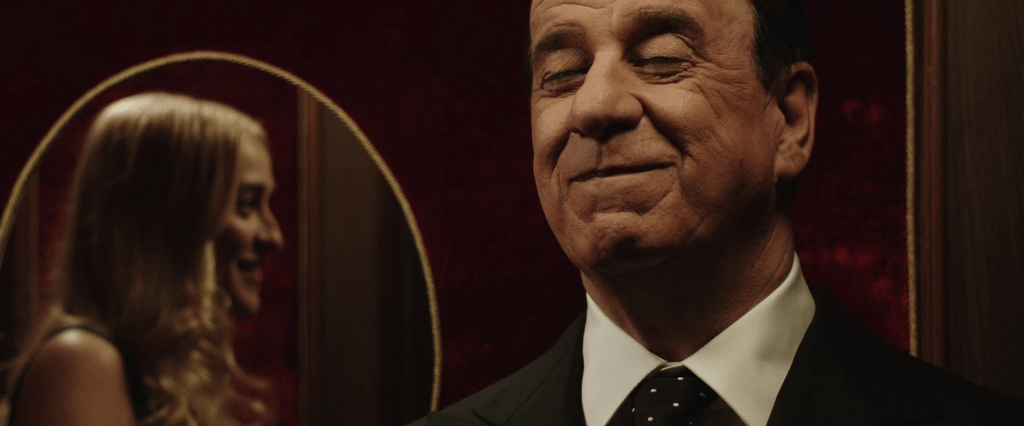

Tony Servillo’s performance as Silvio is one that many people take issue with. I don’t. I think it’s brilliant. It encapsulates Berlusconi’s entire aura as a showman. It ridicules him to the point of total acceptance. Acceptance of the shallow nature of politics. This is it. Silvio’s grotesque mask is what politics amounts to in this world. And Berlusconi would have been the first one to admit it. “Truth is the result of our tone of voice and the conviction with which we speak,” Berlusconi tells his beloved grandson. “The only thing that matters is that you believe me.” That says it all, doesn’t it?

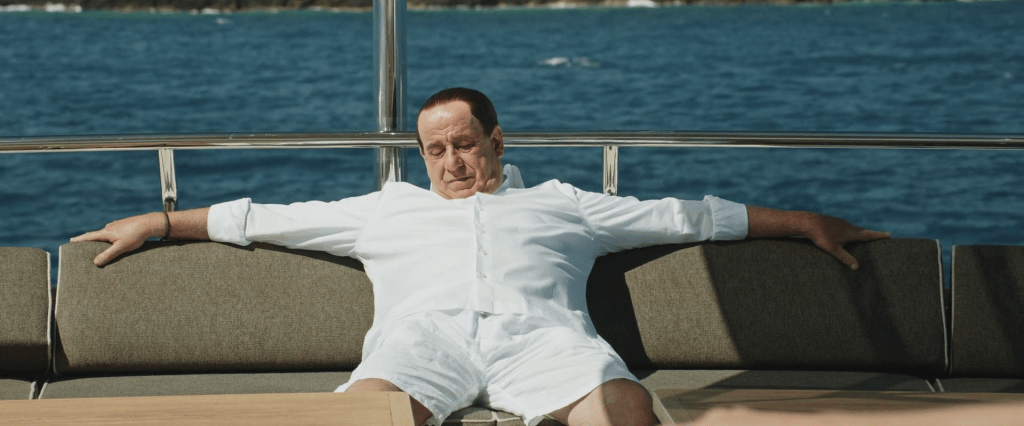

Servillo walks through the movie with an absurd grin, one that stands for happiness and satisfaction as much as it stands for pain and terror. On countless occasions, Berlusconi says, “I never take offense,” but then, with the same painted smile, he proceeds to put a person’s career and livelihood on the brink of destruction for the sake of preserving his own image. Unlike his performance as the infinitely bored yet sincere Jep Gambardella in The Great Beauty, Servillo’s take on Silvio turns Berlusconi’s boredom into the product of a career built on lies. Lies have caused his body and mind to go into decay. Silvio spends his days staring at the horizon with a blank expression on his face and, with the exception of an evening among friends filled with serenades and jokes, his existence amounts to roaming the empty halls of his mansion, wishing for some action, some meaning. Anything.

The most crushing defeat comes in the form of a young girl, Stella, whom Silvio tries to seduce. His failed attempt stems from the fact that Stella is, along with his wife, the only person in the movie to see right through him. “Your breath smells like my grandfather’s,” she tells him. “I’m pathetic for being here and you’re pathetic when you pay me compliments and offer me apologies. Yours is the breath of an old man.” In only so many words, Stella disintegrates the entire image of Silvio as a sex symbol. And, following another fight with his wife, Silvio decides to take the next plane out. When asked if he would like to go to New York, Silvio shakes his head, defeated, and replies, “Naples,” as if he were unable to distance himself from the crowd of devoted followers in the moment of need. His status can only go as far as Italy’s borders. In Naples, he is greeted with a birthday cake and people chanting his name, snapping pictures and blowing kisses. That’s the Italian way.

It’s difficult to imagine this movie working as well as it does in anybody else’s hands. Sorrentino is not interested in Berlusconi’s life. He’s not interested in who he was as a person or politician or business tycoon. What draws Sorrentino to Loro is the implication of a nation that stood watching in awe and stupor as greed, corruption and lies permeated the sociopolitical landscape. For Sorrentino, Italy is a country of spectators and everything that happens, just like in The Great Beauty, is seen as a spectacle to be marveled at. But, unlike the majestic splendor of Rome in The Great Beauty, the world of Loro is hollow and dark. It is made of empty rooms and interior swimming pools, vast golf fields and meaningless garden decorations. It is a world in decay and the public doesn’t know it yet. No. The public is still drooling at the thought of a night spent with Silvio.

Sorrentino’s rendition of Silvio is that of a clown: there is a person behind that make-up but it may be too late to wash it off. The damage has been done, to both him, his marriage and the country. But, the curse continues because at every turn there’s someone willing to give Silvio another chance. At every turn, there’s someone ready to bow down to him, and as the song goes, “Menomale che Silvio c’é” (Just as well Silvio’s here).