At 82 years of age, David Cronenberg continues to be fascinated by the paradoxical nature of our bodies.

The Canadian filmmaker, responsible for such masterpieces as Videodrome, Dead Ringers, The Fly and Crash, has always been bound to the theme of the human body as a vessel of truth and lies, good and bad. The human body – via its shifting trends in perception – being the ultimate expression of who we are as a society. In exploring our relationship with our bodies over the past five decades, Cronenberg has been able to trace society’s deepest fears and insecurities unlike any other contemporary filmmaker.

With the release of his latest film, The Shrouds, a personal meditation on grief (Cronenberg’s wife of forty years passed away in 2017) and the need to know what happens to the bodies of those we love once they’re underground, I decided to revisit one of his most acclaimed films in A History of Violence – a film I found myself thinking about a lot in recent months.

Starring a post-Lord of the Rings Viggo Mortensen at the height of his fame and glory, Cronenberg’s film from 2005 tells the most contrived version of a standard American Hollywood film. It is, after all, one of the oldest stories in cinema’s repertoire: a seemingly honest family man with a dark past whose perfect life comes to a sudden crashing halt with dangerous consequences for his loved ones.

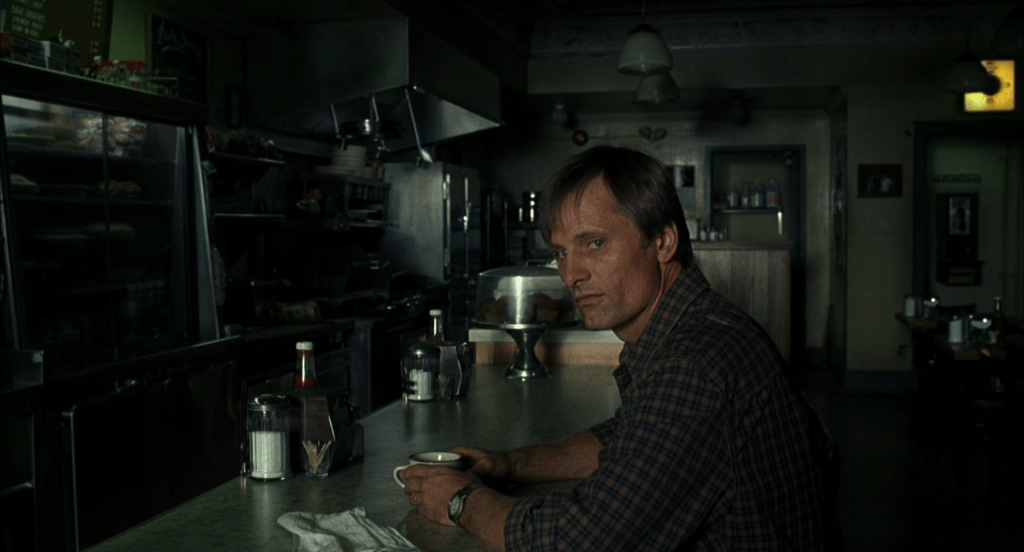

Mortensen plays Tom Stall, the owner of a diner in a small town in rural Indiana, who suddenly finds himself labelled the town’s hero after confronting and killing two robbers. But Stall’s heroic act soon draws the wrong kind of attention as the ghosts from his past come back to haunt him, threatening the balance of his perfectly innocent life.

For anyone that still hasn’t realized, Cronenberg’s film walks the fine line of satire, characteristic of a director who’s always made sure to evade the clutches of the Hollywood system. A History of Violence is quintessential American cinema, or rather the simulation of what an American film is through the eyes of a Canadian filmmaker. It is Cronenberg poking fun at the way similar stories have been told in the past: Hitchock’s Shadow of a Doubt (about a serial killer pretending to be a loving uncle) or Orson Welles’ The Stranger (about a former Nazi officer hiding out in America under a new identity) come to mind, among many others; stories of a world that is too easily fooled by the shiny facade to notice the ugly interior. For a long time after World War II, Hollywood was obsessed about stories of false appearances, yet with time the urgency of such stories was lost, only to return in the aftermath of 9/11.

It was in such a reality that Cronenberg’s film came out and echoed loud and clear. The pathetic yet unavoidable violent nature lies in all of us, seemed to be the filmmaker’s claim at the time.

Twenty years later this claim still rings true. But upon rewatching Cronenberg’s film, I was drawn to the magnificent blend of meditation and humor. Because even though Cronenberg fully acknowledges how ridiculous the story is, how utterly phony some of the elements in it are (such as the subplot involving Tom Stall’s son being bullied at school and, predictably enough, rebelling against the bully, showcasing his father’s violent predisposition), he is still concerned with the protagonist’s plight – that no matter how good of a person one becomes, no matter how loved one is, there is still a past linked to the person we once were. And that past is linked forever to our bodies, to our physical appearance. That is Tom Stall’s predicament.

Unlike in some of his other movies that achieved cult status due to the label of ‘body horror,’ characterized by graphic horror elements of gore and violence, of twisted corpses covered in blood, of strange creatures emerging from our entrails, of monstrous disfigurements and amputations, the horror in A History of Violence lies in Tom’s past as well as the implications on his present life. Because, as much as we like to say that appearances are not everything, in Cronenberg’s mind appearances do indeed mean a hell of a lot. A man like Tom can make up a new name, a new identity, create a warm household and be the father to two children and the husband to a wife who thinks she knows him, and yet everything amounts to a fragile illusion that can easily come undone. That is the real horror.

Our bodies are vessels that testify our experience on this earth. And even though most of our scars can be covered up with surgery, according to Cronenberg there is some fundamental truths we cannot get rid of. In Tom’s case it’s the face – the face which Ed Harris’ character, Fogarty, recognizes right away as soon as Tom’s heroic act is nationally televised, earning him unwanted attention.

Harris plays a gangster who comes to threaten Tom’s idyllic lifestyle. He is the consequence of Tom’s past and the reminder of what Tom’s appearance cannot make go away. In Fogarty’s case, Tom, formerly known as Joey Cusack, tried to rip his eye out with barbed wire. So even though Tom has moved on with his life, Fogarty’s condition, his dead eye, serve as evidence of what a man like Tom is capable of. Cruelty cannot be forgotten. Violence comes natural. It is embedded in our history. “Your husband knows me intimately,” Fogarty tells Tom’s wife, tapping his dead eye with his forefinger. In typical Cronenberg fashion, intimacy is a purely physical bond, which in Fogarty’s case stems from a brutal act of violence against him that will bind him forever to the man who once went by the name of ‘Crazy’ Joey Cusack.

But the physical display of intimacy also appears in Cronenberg’s vision of sex.

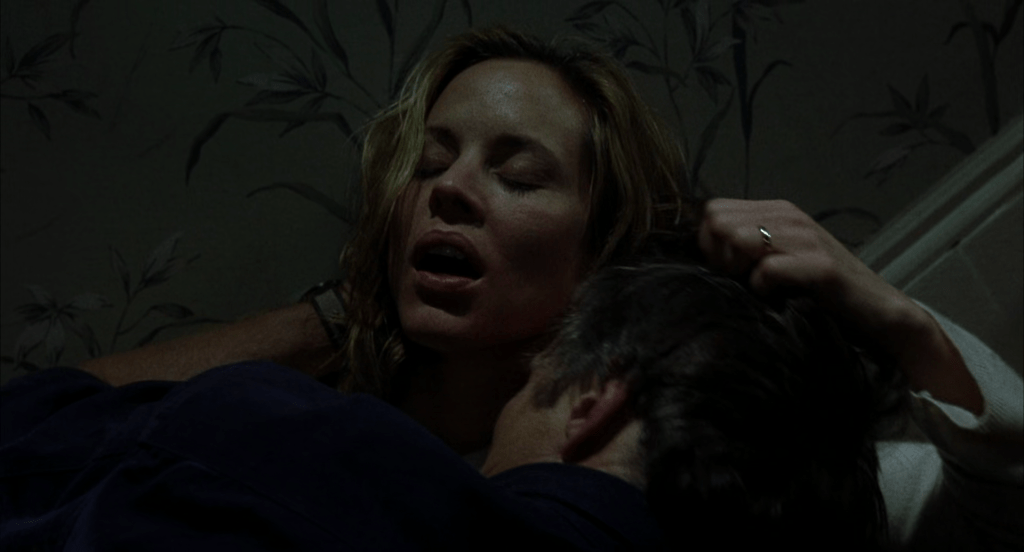

The film contains two scenes of physical intimacy between Tom and his wife, Edie. The first one being the married couple coming together on a night that sees them in a state of teenage euphoria, Tom’s wife literally putting on her high school cheerleader costume, ‘welcoming’ him into her own past. The scene is tender and playful yet also comically cliché – once again, Cronenberg simulates the American way of life depicted in most movies without shaming his characters’ feelings. The scene ends with the husband and wife holding each other in a sleepy embrace, professing their love in gentle whispers.

Later on, after the incident involving Tom killing the two robbers as well as confronting Fogarty in his own backyard, the couple engage in another sexual act. Yet this time the stakes are completely different. And so is the intention on both sides. For Edie it is a farewell to the man she thought she knew, while for Tom it is the expression of who he really is, it is him finally opening up to his wife after years of lies, of make believe. It is him revealing what really lies beneath the shiny facade. Smoke and mirrors. Nothing in this scene rings false. It is a complete turnaround with Cronenberg holding the camera on the act, not drifting away, cutting or fast-forwarding past the explicit gasps and grunts. It is him wanting to confront the painful consequences of Tom’s past coming back to haunt him and those he cares about the most. The real tragedy lies in the pain we inflict on the ones we love, and in the scene this pain is literally translated into Edie having her back bruised from the wooden staircase they fucked on.

Not for nothing the film is based on a graphic novel. The comic overtones as well as the emphasis on the purity of small town America, ‘the good people’ behind it and the evil forces that threaten them are all there to showcase Cronenberg’s talent at adapting other authors (Cronenberg’s screenwriting resume is impressive, having adapted works by Stephen King, William S. Borroughs, Don DeLillo, JG Ballard, among others) but also to further highlight the disparity between the made-up vision and the real-life counterpart. Violence carries weight – its effects are grotesque and nasty, with Cronenberg never shying away from depicting the graphic result of a bullet to the head or a deadly blow to the face. Even though the entire structure of the film resembles that of a comic book, the themes discussed in it are complicated. The human body is ugly and beautiful at the same time for all the wrong reasons, argues Cronenberg. It is a physical box of organs, blood and bones and also the vessel through which we express things that go beyond the physical aspect of who we are. Yet, whether we like it or not, we remain tied to these bloody bags of bones. We cannot escape, no matter what we do. No matter who we love or kill.

Tom is a good man, or so he appears to be. Yet we also learn things about him that cast a dark shadow over him and the new life he’s built. Cronenberg’s neo-noir follows the genre’s traditions of asking us, the audience, several bothersome questions. How come we cheer for Tom to succeed? How come the violence he inflicts on others comes across as justified and righteous? It is this paradox that Cronenberg wants us to face. Audiences have grown to believe in myths. But what if these myths are fallible? What then?