How does an actor reinvent himself if he’s so deeply embedded into the core of pop culture? How does one escape the grip of fame to explore his own range as a performer and by doing so subvert everyone’s expectations?

The answer is: you work damn hard at it, regardless of the risk. The risk being to slip away from the public’s adoration and possibly compromise one’s own career. This used to be a very prominent trap for actors in the studio system of Golden Age Hollywood. Because there is nothing that Hollywood loved and continues to love more than boxing its brightest stars in a well-defined, bubble-wrapped frame that meets audience’s expectations and guarantees a good turn-out at the box office. Such was the case of actors like Clark Gable, Gary Cooper and later on Burt Lancaster and Rock Hudson. That could have been the case for James Stewart had the Indiana-native not given himself away to director Anthony Mann in the early 1950s, turning his beloved, honest on-screen persona upside down and adding new shades to his repertoire. The result was a complete career makeover for Stewart who, after starring in beloved crowd-pleasers such as It’s a Wonderful Life, Harvey and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, was in need of a challenge, one that could extend his career and stimulate his acting skills. In order to do that, however, Stewart needed to break America’s heart.

The turnaround happened in 1950 when Stewart worked with Anthony Mann for the first time on Winchester ’73, a Western about a man intent on getting back his precious rifle. Mann wasn’t interested in presenting the world with more heroes. He wasn’t looking for the great, honorable protagonist to save the day and do so by sticking to a certain moral code. And he wasn’t looking for epics either. What Mann was interested in was the murky, dubious nature that characterized and chewed at the mythology of the American West.

Coming from the world of hard-boiled noir and crime films, Mann applied the same ideas to the Western landscape, blending characters’ motivations and refusing to give out too much backstory. Mann liked to keep things unclear, allowing his characters’ actions to do the talking. As opposed to John Ford, Mann did not believe in noble values as an essential component of the way the West was built. Ford saw nobility and grace sprout in spite of violence, whereas Mann confronted violence at face value: he saw it as the truth about who we are. There was no greater reveal in Mann’s films than a man committing a violent act and embracing its consequences.

For Mann, Stewart was the perfect actor. He was clean-cut, had been the poster boy for Frank Capra’s movies, and was an all-around American hero following his service during the war. Stewart was also moving into his forties, a dangerous territory for any actor, including his good friend Henry Fonda; the roles of Prince Charming were to bound to dry up at any moment for guys like Fonda and Stewart.

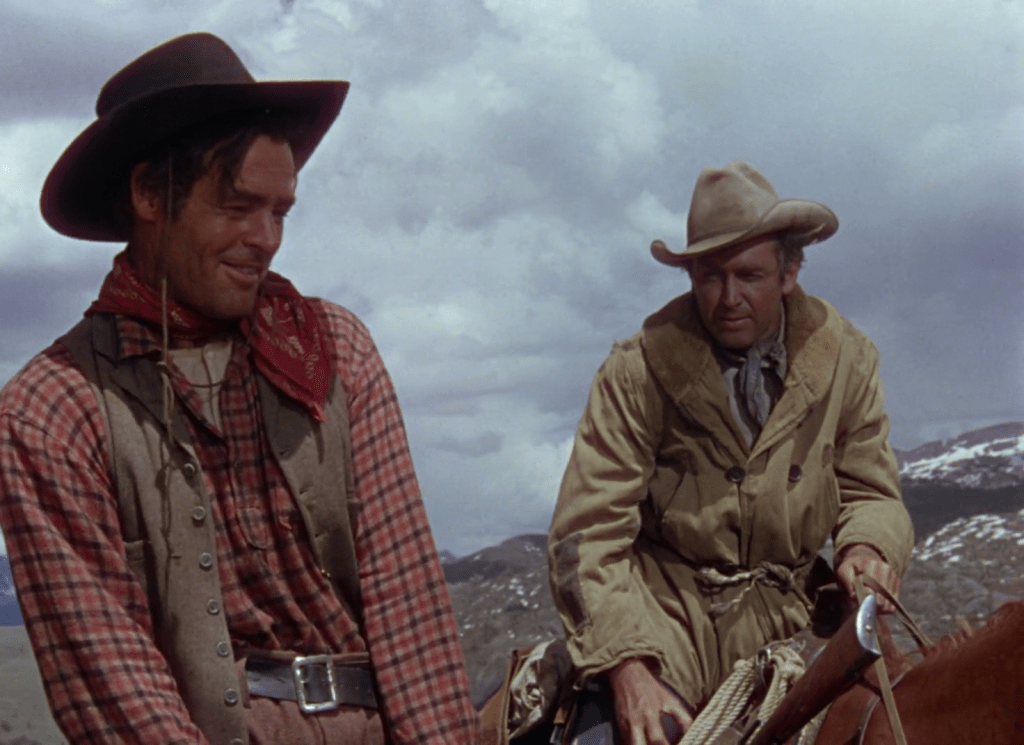

When 1953 came around, Stewart was on his third collaboration with Anthony Mann, and my favorite of theirs – The Naked Spur – a Western about a bounty hunter determined to bring a criminal to justice. By this point, Stewart was already fully committed to his new on-screen persona and seemed to take pleasure in betraying the audience’s ideas about him.

In the film, Stewart plays Howard Kemp who is out to arrest outlaw Ben Vandergroat (an excellent Robert Ryan) – a killer and horse thief who holds a personal beef with Kemp. The two appear to know each other, though it remains unclear to what degree or why their paths crossed. Normally, Stewart would have played the character straight, with grace and a sense of honor that would have distinguished him as the ‘good guy’ in the movie. But with Mann directing, Stewart comes off as off-putting and pathetic. There is not an ounce of charm in Kemp’s entire body. He doesn’t shine when pitted against the other disgraced characters in the film.

Kemp’s motivations are only brought forth when Vandergroat decides to taunt him and put him in a bad light. There is talk of a woman leaving Kemp and taking away his ranch, but there is seldom any scene in which Kemp comes off as the sympathetic, honest and down-to-earth rancher. Stewart doesn’t stammer his lines the way he did in the past. He doesn’t play into the persona of the affable gentleman from The Shop Around the Corner, nor does he show the good-natured, empathic spirit of George Bailey from It’s a Wonderful Life. Instead, he opts for a mix of cruelty and awkwardness. We can see Kemp be uncomfortable with who he is and what he’s driven himself to do. He’s not fooling himself nor anyone else. That’s what Stewart is able to show in Mann’s cinema: the acceptance of his character’s fallibility.

It is a performance of a man who wants to shed his own skin. Kemp, much like Stewart at the time, is a decaying relic of the past. For Stewart, the 50s presented opportunities that his younger self would have failed to seize. And though he is only forty-five in the film, Kemp looks much older and weary if compared to Robert Ryan’s character – Ryan was just a year younger than Stewart but holds the screen with the grin of a man twenty years his junior. Ryan’s swagger perfectly complements Stewart’s unease and serves to further highlight the complete shift in the latter’s performance. While Ryan exudes cool, Stewart tests the audience to see how far they’re willing to follow him in his quest.

One could argue that Clint Eastwood’s performance as William Munny in Unforgiven was modelled after Stewart’s turn here, or any other film he made with Anthony Mann. Both William Munny and Howard Kemp are men pretending to be someone they’re not. Both characters are just as murky and dangerous as their enemies. It is hard to tell, both in Mann’s cinema as well as Eastwood’s, where good and bad lie; their vision is primarily concerned with the study of the grey zone where characters like Kemp or Munny carry on with their miserable lives. Because that’s what’s hardest about it all – these imperfect men, driven by primal impulses of violence, have to somehow go on living. Like Ryan’s character says to Stewart’s, “Choosin’ a way to die? What’s the difference? Choosin’ a way to live – that’s the hard part.“

What’s most incredible about Stewart’s performance is that he completely abandons any sense of ego. The turn he gives feels like it’s the product of grueling labor, of the actor stripping himself of all the qualities that made him recognizable in the public eye. There are moments scattered throughout the film which see Kemp take hold of his guns and point them at others as a threat. Each time he does it it is the body language of a desperate loser whose last resort has now become his sole means of expression. Stewart as Kemp is unable to hold anyone’s gaze for longer than a few seconds – it’s as if we’re watching an A+ student learn to become a bully and get embarrassed time and time again. Stewart’s act is a very dangerous one, but the actor never falls into ridicule. He embraces Kemp’s inadequacy and imperfect character arch without ever falling back on his old tricks. It is never George Bailey that we see before us – it is always, unfortunately, the grim, disturbed expression of Howard Kemp.

Stewart’s performance in The Naked Spur is one of many great performances in the film: the underrated Ralph Meeker plays an equally disturbed and greedy cavalry officer, while veteran actor Millard Mitchell gives a convincing turn as an out-of-luck gold prospector. That is to say – nobody ever shines above the rest in an Anthony Mann movie because the director never felt the need to put anyone on a pedestal. All characters are equal in Mann’s cinema – there is no grand finale, no great moral lesson. It is all complicated and often disappointing, because that’s how life in the American West was.

Going back to Stewart and Mann’s collaborative catalogue, it is amazing to see a Hollywood icon head in the opposite direction of the likes of John Wayne and Humphrey Bogart: guys whose image towered over the movies they made. Stewart, on the other hand, seems to have realized that in order to get challenging parts, one must be willing to compromise one own’s stardom, take the leap without a safety net. Moving from Frank Capra’s prestigious productions to Anthony Mann’s small-scale Westerns was a leap that few actors of Stewart’s caliber at the time would have made.

And although we still think of Stewart as the face of the all-around good American, model father and husband, we also can go back to see for ourselves what the actor thought of this association. The answer is: not much. Following his work with Mann, Stewart was still tempted to test his abilities. That is why he reunited with Alfred Hitchcock three times in the 50s, making some of his greatest films, including Vertigo, which borrows heavily from the persona Stewart created with Anthony Mann’s help. All of a sudden we’re no longer watching a man hold life’s secrets. On the contrary – we’re watching a man struggle to find his place in the world. And what is more relatable than that?