One of the most challenging aspects of our lives that cinema can try and capture is teenagehood. After all, being a teenager is complicated. Everything changes within you. The world stands still – or so we think – and watches as you grow, as your facial features change, as you mature and make mistakes, one after the other. You change not because you want to but because you have to. It’s natural. And with this change comes greater responsibility despite the mythic illusion of freedom we keep selling to each other. Our childish certainties become frail and are soon torn down by the latest trends we buy into and the new people we meet, the new experiences we make, and the memories we collect along the way.

Movies have often struggled to tell the story of lost innocence, because that is what teenagehood is: young people coming into contact with reality. One of the few movies I can think of that captures the turmoil of those years is Maurice Pialat’s film from 1983 A Nos Amours – an erratic study of a girl seeking love at every turn and the film that launched the career of Sandrine Bonnaire who would go on to collaborate with French masters such as Agnes Varda, Claude Chabrol and Jacques Rivette.

Bonnaire plays Suzanne, barely fifteen years old the first time we meet her and already restless. She is at summer camp, and in-between learning lines to a play she meets up with her boyfriend. Daily escapades to the countryside with the hope of losing her virginity to Luc result in Suzanne coming to the conclusion that sex is physical, there’s not much to it, eventually breaking up with Luc after an episode of unfaithfulness with an American tourist. Despite being only 15 years old, Suzanne is sharp and observant. When the American awkwardly thanks her for ‘offering’ him her virginity, Suzanne coldly retorts, “You’re welcome. It’s free.”

Pialat’s movie is purely impressionistic rather than an accurate and steady portrayal of teenage angst. His camera places Suzanne at the center of every frame, only for her to be swallowed up by the shadow of a male figure. Every man in Pialat’s movie wants to tame Suzanne and define her on his own terms. The great irony of teenagehood is that we are supposed to follow a certain path laid out for us by adults who are most of the time unable to meet us half-way. It’s a complex web of misunderstandings and disagreements. A teenager like Suzanne is impossible to hold still and define in one sentence, yet everyone takes a shot at it, trying to take advantage of the beautiful smile she’s been complimented on since she was a little girl. She is a fleeting, scattershot presence, almost a ghost in the lives of people who would do anything to get ahold of her.

Suzanne’s family life is a disaster-zone. Her parents – with their marriage on the brink of collapse – are constantly fighting each other, and her brother has grown increasingly violent toward her.

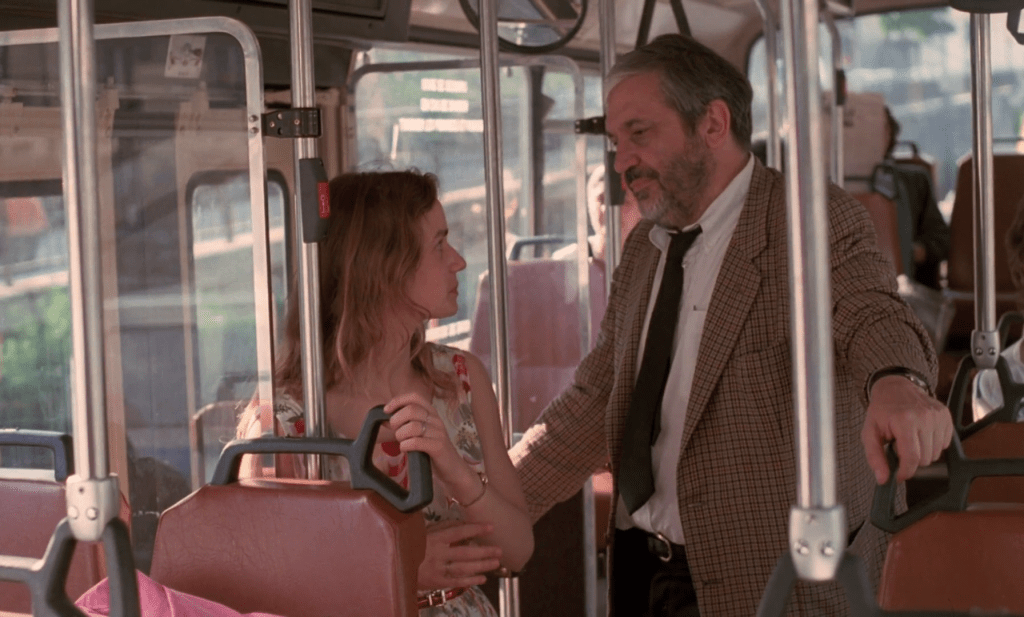

Pialat himself plays the father: he’s a frustrated tailor, grown weary of his job, his own surroundings, his own choices that have driven him to exhaustion. The French director plays the role beautifully, and remarkably the movie comes alive in the few instances that the father and Suzanne spend together, studying each other carefully like wild animals, sharing moments of vulnerability in a home where violent, abusive outbursts are the bread and butter of its inhabitants. The father comments on the fact that Suzanne doesn’t smile as much as she used to. Suzanne also observes that her dad is sad. “I’m not sad. I’m tired,” he replies. “I think I’m going to move out.” Both of them notice small yet life-altering changes in each other, setting their differences aside for one brief moment and acknowledging the fact that this instance of shared vulnerability is far from guaranteed and must be treasured. It also hints at the father preparing to withdraw into the darkness, his journey coming to an inevitable end, whereas Suzanne is only getting started. Will her smile ever be the same again?

Suzanne acts throughout the whole movie. After all, what are teenagers most known for? Probably their ability to lie and act, wishing to simultaneously conform and rebel against people’s expectations. That’s what Suzanne does. She embraces the same people she’s fleeing from. She adapts according to the cards she’s been dealt. She jumps from one romance to another, clinging to the male figures that dominate her world. Her strength is also her weakness. This compulsion to hang onto others results in her suffering whenever someone lets her down. And let-downs are a frequent occurrence in the lives of teenagers who are not yet equipped and skilled enough to avoid the bumps and bruises along the way.

What is most upsetting and honest about A Nos Amours is the clash between Suzanne’s perception in the outside world and in her own home. Her mother, unable to cope with her own marital situation, vents her anger, her deepest, most venomous hatred at Suzanne, who finds herself cornered by her own brother’s physical abuse and emotional manipulation. Outside she may be the biggest prize of all, the most beautiful and lively soul in Paris, yet within her own home she is seen as nothing but a slut, a tramp, and an unnecessary addition to the family – a burden for life. Suzanne’s crystal clear presence around strangers is replaced by that of an insecure, panic-stricken little girl whose only dream is to escape this domestic hell.

But what I most admire about Maurice Pialat’s film is that it never hammers the message home, instead it lets Suzanne’s life unfold the way life of a teenager does. Scenes – which are mostly improvised without a script as Pialat rarely worked with a finished screenplay – don’t hold any emotional payoff and yet it’s not a documentary, it’s Pialat painting the canvas with a girl’s life. A simple concept, isn’t it? Yet, the execution, the instances it decides to capture – Suzanne, bitter about a lost love, sitting at a bus stop in the pouring rain, or deciding to sleep naked against her mother’s wishes – are so unique and completely grounded in the reality of the character it presents that it makes me wonder, how often do we see this level of commitment to fictional characters nowadays? Pialat’s vision, as critic Kent Jones wrote, is all about the here and now. In this case, it’s about the fleeting moments of Suzanne’s coming-of-age. It may not be glorious and happy as movies like Boyhood would have us believe, but it’s real. For Pialat, reality and the possibility to capture a miniscule fragment of it and replicate it on the screen meant more than anything else.

As I am thinking about the concept of ‘here and now,’ I realize how A Nos Amours deliberately skips over the monumental steps in Suzanne’s life including her wedding. There is no timeline for us to refer to, no points of reference to guide us in her odyssey… the loves in Suzanne’s life come and go, what stays is her insatiable need to be loved. As her cynical father tells her, “You think you’re in love, but you just want to be loved.” Isn’t that what being a teenager is all about? The projection of one’s own fears on someone else’s feelings, the thirst for attention, for care. The illusion of being tender and loving with someone whom we’re not entirely sure deserves it in the first place. Suzanne’s father knows the dangers that this inability to fill one’s own sense of self-worth may bring. But, on the other hand, he knows Suzanne’s story is far from over. It’s only the beginning. Adolescence is just a small step, and the loves we formed, or thought we’d formed, are only part of the prologue.